When Ed Temple headed off to college at what was then called Tennessee Agricultural and Industrial State University, he didn’t know what to expect. A Pennsylvania native, he had never before experienced life in the segregated South. Nevertheless, he stayed in Nashville following his graduation, landing a job as women’s track coach at his alma mater, now known as Tennessee State University. In a career lasting more than four decades, his Tigerbelle teams won 34 national titles. Forty of those women he coached competed in the Olympics, winning 23 medals. Looking back on his life and career, he said: “In the end, it turned out all right. I have no regrets.”

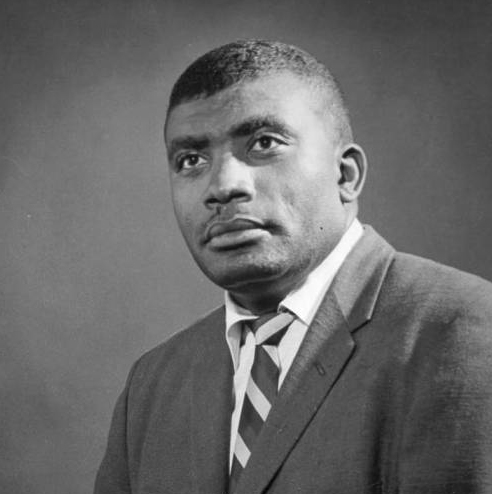

Edward Stanley Temple

Born: September 20, 1927

Died: September 22, 2016

Education: John Harris High School, Tennessee State University

Career: Tennessee State University - Tigerbelles (women’s track team) coach from 1950 through 1994

Notably:

- 44 years as TSU's women's track coach

- 40 of the women Temple coached competed in the Olympics, winning 23 medals

- Won 34 national titles

- 16 indoor titles

- 13 outdoor titles

- 5 junior championships

- An all-state athlete in football, basketball and track in high school

Ed Temple made it ‘so hard to be a Tigerbelle’ – and they loved him for it

More than 20 years after his retirement, it’s hard to spend much time around the Tennessee State University campus without seeing or hearing Ed Temple’s name.

A drive to TSU’s North Nashville campus from Clarksville Pike takes motorists along Ed Temple Boulevard. The campus library has an exhibit dedicated to Temple prominently displayed near one of the main entrances, a bronze engraving on a staircase landing, two rooms filled with his memorabilia and an office reserved for the legendary track and field coach’s use.

The university annually hosts Edward S. Temple seminars on society and sports. And, of course, there’s the Edward S. Temple Track, where each year new crops of track and field athletes aspire to continue the legacy Temple built.

That legacy is astonishing: Temple coached TSU’s Tigerbelles, the women’s track team, from 1950 through 1994. During that time, his teams won 34 national titles – 16 indoor, 13 outdoor and five junior championships. Forty of the women he coached competed in the Olympics, winning 23 medals. He coached two of those Olympic teams, in 1960 and 1964, and was scheduled to serve as a coach on the 1980 team that boycotted the competition due to the Soviet Union’s invasion of Afghanistan.

Not bad for someone who was lured to TSU as a college student under a somewhat misleading pretense.

“In the end, it turned out all right,” Temple said of his career. “I have no regrets.”

‘Didn’t know what I was getting into’

Growing up in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, a career as a women’s track coach and a life in faraway Tennessee weren’t on Temple’s mind. An all-state athlete in football, basketball and track in high school, he dreamed of attending Pennsylvania State University. And his parents were more interested in having him pursue the musical talents he demonstrated in the John Harris High School band.

“My parents really didn’t want me to participate in track,” Temple said during an interview in the spring of 2015. “My mother had worked hard to pay for trumpet lessons and she didn’t want that money to go to waste.”

Temple’s life was forever changed when a neighbor, Tom Harris, announced his plans to take a coaching job at TSU, then called Tennessee Agricultural and Industrial State University. Harris told Temple that Leroy Craig, one of Temple’s athletic rivals, was planning to attend TSU.

Temple decided that if TSU was good enough for Craig, the school must be good enough for him, too. It wasn’t until later that Temple learned Harris had used a similar line on Craig – and got a similar response.

For a young black man who had never been farther south than Washington, D.C., moving to the segregated South to attend college during the 1940s was a culture shock. Being relegated to the back of the buses and required to use the side entrances of theaters was a new experience for both Temple and Craig.

“Leroy Craig and I just shook our heads,” Temple said. “I didn’t know what I was getting into until I got to Nashville.”

Temple was determined to make the best of the situation, though. He and Craig roomed together on the same floor of the same dormitory for their four years as undergraduate students. In fact, Temple was still living in the dorm after earning a degree in sociology and searching for a job as a high school football or basketball coach.

Harris left TSU for another coaching job at a college in Virginia and recommended Temple as his replacement. When Temple was called to the university president’s office to discuss the job opening, he initially thought he was being kicked out of his dorm room.

Walter Davis, TSU’s president at the time, had a different agenda. He hired Temple to coach the women’s track team and work full-time in the school’s post office while pursuing a master’s degree. In his 1980 autobiography, “Only the Pure in Heart Survive,” Temple credits Davis with being “broad-minded” enough to support the women’s track team, although “if he’d had any idea that would ever surpass football, he wouldn’t have turned it loose.”

A humble start near a dump and a pig pen

In the beginning, there seemed little danger of that happening. Temple was hired in 1950 at a salary of $150 per month and his first-year budget for the track team was only $64. He had only a handful of athletes to work with and no scholarships to offer to recruit more.

The training facilities consisted of an incomplete cinder “half track” located near the agriculture department’s pig pen and a dump site. “Running a 440 (meter race) was out of the question,” Temple wrote, “and on hot days down there by those pigs you sort of lost your motivation to run much of anything.”

From the very beginning, Temple was under no illusions about where women’s track ranked in the TSU athletic department’s pecking order: Football and basketball were the stars – and women’s track and the other sports programs got “the crumbs that were left.”

Some might wonder why Temple didn’t move back North or at least find a better job near where he was living. But Dwight Lewis, a longtime journalist for The Tennessean newspaper in Nashville, said options for black coaches were much more limited at the time.

“Where else was he going to go?” Lewis said in an interview. Despite the limited financial resources TSU devoted to the track program back then, Lewis said Davis was committed to building the university’s reputation through its sports programs.

And while Temple had excelled at team sports as a youth, track had a different kind of appeal.

“Track is an individual sport,” Temple said. “You’re on your own. When that starter says, ‘on your mark,’ it’s you.”

Success didn’t happen overnight. Although Audrey ‘Mickey’ Patterson had become the first TSU woman to win a medal in the 1948 Olympic games, the program Temple inherited was no powerhouse.

Although his budgets for the team gradually increased to a few hundred dollars a year, that was only enough money to attend one or two events. One of those was sponsored by the Tuskegee Institute, which then represented the gold standard for women’s track at black universities.

“For four or five years, we got beaten on like a drum,” Temple said of those early years. “Tuskegee was a power.”

Temple, always a pragmatist, made the best of the resources he had. Lacking the money for fancier transportation, the team traveled to events by station wagon. Since segregation severely restricted the places they could stop while traveling, they packed their meals and took bathroom breaks in fields along the side of the road.

In 1953, the team traveled to a meet at Madison Square Garden in New York City, but wasn’t able to practice at the arena the night before because the circus was in town. Temple improvised.

“We practiced in the halls of the Paramount Hotel,” Temple recalled. “Shoot, I told them we hadn’t come all that way for nothing.”

Temple describes Mae Faggs, a sprinter who had competed on the 1948 Olympic team while still in high school, as his first big-time recruit.

Faggs, who lived in Bayside, New York, was short but extremely self-confident. She was known to approach the starting line at races declaring, “I’m gonna be first – who’s gonna be second?” In his book, Temple described Faggs as a “stick of dynamite.”

Faggs was recruited by other schools, including Tuskegee, but Temple said TSU was closer to her New York home. Although Faggs experienced the same type of “culture shock” that Temple had gone through when moving to the segregated South, she endured and became one of the Tigerbelle program’s many stars.

In the 1952 Olympics in Helsinki, Finland, Faggs and future Tigerbelle Barbara Jones each won gold medals.

‘It’s so hard to be a Tigerbelle’

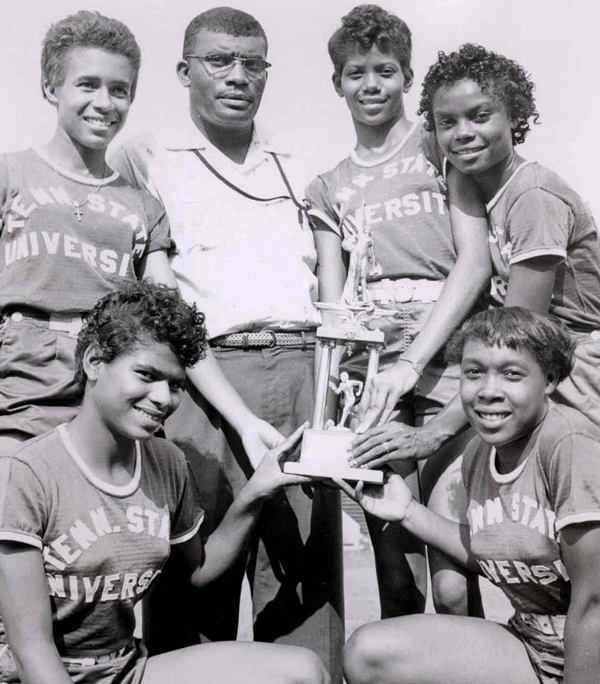

A & I State University display the medals they won in a track meet against the U.S.S.R in Moscow in 1958. Pictured are Coach Edward S. Temple, Martha Hudson, Lucinda Williams, Isabelle Daniels and Margaret Matthews.

In the early years of the program, Temple didn’t have scholarships to lure athletes to Nashville. Decades later, federal legislation known as Title IX would require universities to make substantial increases in funding for collegiate women’s athletics – including money needed to provide scholarships. But when Temple took over the program in the 1950s, he joked that “we didn’t even have Title I.”

Instead of scholarships, Temple offered his athletes work-study programs. Some of them had jobs in the campus post office under the supervision of Temple and his wife, Charlie B., whom Temple had met while he was a student at TSU. Others worked elsewhere at the university.

One of Temple’s most effective recruiting tools was the summer training program he started for high school girls. That program gave him an opportunity to evaluate and develop the talents of future TSU prospects.

The summer training program also tested participants’ commitment to track and field. Practices were held three times a day – at 5 a.m., 9:30 a.m. and 2 p.m. – in heat so intense that the athletes had to tape their hands to avoid scalding them on the track as they got into their starting stances for races.

Wyomia Tyus, who would later win gold medals in two different Olympic Games, first met Temple when she was competing at a track meet in Georgia at age 14 or 15. Temple invited Tyus to attend the summer program – an invitation she accepted but later regretted.

“It was just brutal,” Tyus said of the three-a-day practices. “I just thought, ‘this man has got to be crazy.’”

Tyus said she wanted to come home, but her mother wouldn’t let her.

“As the weeks went on, I felt better about myself,” Tyus said. “I don’t know that I felt better about him.”

By the end of the summer, Tyus said she couldn’t wait to come back the following year.

Lucinda Williams Adams, who would later win a gold medal in the 1960 Olympics as part of a U.S. relay team made up entirely of TSU women, described a similar experience. She accepted Temple’s invitation to join the summer program after her high school team from Savannah, Georgia competed in a meet in Tuskegee.

Adams said Temple’s stern and driven demeanor led her to consider quitting as well.

“We thought he was the meanest person in the world at that initial meeting,” Adams said.

Temple’s training methods were so grueling that they gave birth to a song called “It’s So Hard to be a Tigerbelle,” which his athletes would sing to help them cope.

Coach Temple’s way

Temple was a stickler for rules – and he expected them to be followed. He often told recruits: “There’s a right way, the wrong way and Coach Temple’s way.”

Coach Temple’s way meant always showing up on time and following his instructions. Adams recalls one time when the team took an unscheduled detour through a peach orchard on one of its practice runs. Wilma Rudolph, who would become arguably the most famous of the Tigerbelles, got hung up on a fence and disturbed a bee’s nest. Although Rudolph’s speed was great enough to win her three gold medals in the 1960 Olympics, she apparently wasn’t fast enough to outrun those bees.

Adams said Rudolph got stung several times. When the team returned from the run, Temple was about as mad as the bees had been.

“I thought he was going to send us all home,” Adams recalled.

Temple also stressed the importance of achieving in the classroom as well as on the track. He got regular reports on his athletes’ academic progress. Temple relayed the good news and the bad news about their grades in front of the whole team.

“I’d pat you on the back when you did good,” Temple said. “And when you didn’t do good, I’d talk about you.”

Reflecting back on the successes of his career, Temple proudly noted that all of his Olympic athletes graduated from college.

“Athletics opens doors,” Temple was fond of saying, “education keeps them open.”

Temple also had a rule against underclassmen riding in cars with friends, figuring that they were more likely to find their way into trouble if they did. Lewis, the former journalist at The Tennessean, said that rule applied even to nontraditional students who were considerably older than their classmates.

And Temple asked his athletes to clean up and fix their hair and makeup before giving media interviews after events. Temple said he felt it was important for his women to be seen not only as great athletes, but also as feminine.

“His rules were hard and fast,” Tyus said. “He said, ‘if you don’t follow my rules, I’ll send you home on the train with a comic book and an apple.’”

Those rules applied to everyone, even the star athletes.

Willye B. White found that out the hard way. White had won a medal in the 1956 Olympics while still in high school. Fun-loving and flamboyant, White was nicknamed ‘Red’ because of her often-changing hair colors.

Lewis said White earned Temple’s ire for frequently breaking curfew, drinking and hanging around with older boys.

Lewis said Temple kicked White off the team after six months, telling her: “Red, this campus is not big enough for both of us. And I’m not going anywhere.”

White’s 2007 obituary in the New York Times included a quote from her about her relationship with Temple: “Coach Temple wanted to control every aspect of your life, and I was too much of a free spirit for that.”

Despite their history, Temple coached White on two Olympic teams following her departure from TSU. In 1964, White was part of a four-woman relay team, along with TSU athletes Tyus and Edith McGuire Duvall, which won the silver medal.

While Temple was tough, he and his wife were also like surrogate parents to the Tigerbelles. Duvall said Mrs. Temple baked cakes for each Tigerbelle’s birthday. The Temples also hosted end-of-summer cookouts for the team, although those outings included some time devoted to track film study sessions.

Temple urged his athletes to watch their weight – saying he wanted “foxes, not oxes” – but he didn’t have strict dietary requirements for them. Team members were able to follow eating habits that suited their needs, particularly on meet days.

For example, Temple joked in his book that Tyus “practically trained on Oreo cookies. She hardly ate anything else for the Olympics.” Tyus didn’t dispute that statement when asked about it decades later.

“I was a junk food eater,” Tyus admitted. “I always said that I did that because I grew up on a dairy farm. I ate healthy as a child.”

Tyus said Temple’s approach to training or diets didn’t change for athletes who made it into Olympic competition.

“He always felt that what had gotten us there already, he didn’t want to change,” Tyus said. “He never put us on diets or anything.”

From unknown to icon

Five years into his tenure as coach of the Tigerbelles, Temple’s recruiting and training methods began to pay off in a big way.

In the 1955 Pan American Games, Tigerbelles Mae Faggs and Isabelle Daniels each won silver medals in individual sprinting events. Barbara Jones, who would officially join the Tigerbelles’ roster the following year, won two individual golds. And the three TSU women teamed with another runner to win a gold medal in a relay race.

Also in 1955, TSU won its first national championship in track and field. Temple recalled that the reaction on the TSU campus at the time was underwhelming.

“The 1955 nationals were the first championship any sports team at TSU had ever won that wasn’t limited to black schools,” Temple recalled in his autobiography. “We returned to school to a ‘So what?’ attitude, which only made me more determined.”

That breakthrough year was no fluke. The program continued to win national championships every year through 1968. That streak finally ended in 1969 when the Tigerbelles lost the nationals by a single point.

In the 1956 Olympics in Melbourne, Australia, a relay team made up of Tigerbelle teammates Faggs, Daniels, Margaret Matthews and future Tigerbelle Wilma Rudolph took home a bronze medal in the 400-meter event. (High schooler Willye B. White, still three years away from her short stint with TSU, won a silver medal in the long jump that year.)

Even greater international successes were still to come.

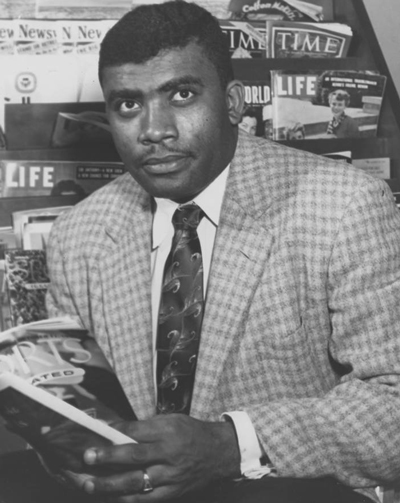

In 1958, Temple talked TSU officials into providing a chartered bus for his athletes who were hoping to qualify for the national team at an event in Morristown, New Jersey. After years of traveling by station wagon, Temple said the bus was “like being in a 747.”

The trip was a productive one, with eight Tigerbelles qualifying for the national team that was scheduled to compete in an event in the Soviet Union. The women’s team didn’t yet have a coach, though.

Temple, who hadn’t been invited to coach his athletes on the 1956 Olympic team, seized the opportunity. After the qualifying event, Temple pulled aside Frances Kaszubski, chair of the women’s team. He told Kaszubski that if he wasn’t selected as the coach, he and his athletes would get back on their bus and head home.

Kaszubski went into her committee meeting to discuss the selection of the next coach. “She came back in two minutes and said, ‘Ed, you’re the coach,’” Temple recalled.

The Tigerbelles went into the meet as underdogs to the Soviet team. During a news conference prior to the event, Temple recalled that most of the questions were directed at the coaches of the U.S. men’s team. When Temple finally got questions, they had more to do with race relations than sports.

When a reporter asked Temple how many black athletes were on the team, Dan Farris, executive director of the Amateur Athletic Union (AAU), responded that they didn’t know “because we are just one family.” Temple, noting the irony that he couldn’t even order a hot dog at a lunch counter in his own country at the time, later wryly noted in a speech that “it was a revelation for me to go to Russia. I had to go there to find out we were all one big, happy family!” Despite the low expectations, the American women did well on the trip, winning several events.

Temple’s athletes followed up the next year with 13 medals in the Pan American Games, leading up to the 1960 Olympics in Rome.

A star is born

A & I State University pose in their U.S. Olympic track suits with coach Edward S. Temple. Pictured are Isabelle Daniels, Barbara Jones, Lucinda Williams and Wilma Rudolph. Coach Temple is wearing his 1959 Pan-American Games jacket and holding a 1956 United States Olympic book.

Following their bronze medal win in the relay at the 1956 Olympics, the Tigerbelles wrote a letter back home to Temple. Rudolph, then still a high school student, signed the letter as “your future star.” Those words turned out to be prophetic four years later.

Up until that year, Temple considered Rudolph – known as “Skeeter” to her teammates – to be a good but not great athlete.

“Wilma really hit her peak in 1960,” Temple said. “Up until that time, I had three or four girls on the team who were better than her.”

After winning a silver medal in the 100-meter sprint in the 1959 Pan American Games, Rudolph ran one of her fastest times in a race before the 1960 Olympics. At the time, Temple remembered thinking that maybe her time had been so fast because someone had incorrectly measured the track and it wasn’t quite 100 meters long.

Then Rudolph won the Olympic qualifying event at the same distance. Temple’s reaction? “I’m saying to myself, ‘It’s hard for two tracks to be that short.’”

The 1960 Olympic Games were Temple’s first as coach of the women’s team, but he doesn’t remember feeling a lot of anxiety when he and the team arrived in Rome.

“We weren’t expected to do anything, so there was no pressure on us,” Temple said.

Rudolph certainly didn’t show any nerves leading up to the finals in the 100-meter event. In fact, for a short time, U.S. officials were having a hard time finding her prior to the race. When they did, Rudolph was asleep on a rub-down table in the locker room. “She was cool,” Temple said.

Rudolph won a gold medal in the 100-meter event, then later in the 200-meter. After that point, she really wanted to win a third gold in the 400-meter relay with her three Tigerbelle teammates, Martha Hudson, Barbara Jones and Lucinda Williams Adams.

Adams ran the third leg of the relay, with Rudolph handling the final anchor leg. Temple said the Tigerbelle team was running in third place when Rudolph was passed the baton.

Adams recalls that the baton handoff almost resulted in disaster as Rudolph bobbled it momentarily. “Once she got that baton, she was gone,” Adams said.

Rudolph’s closing run resulted in her third gold medal, with new Olympic records set in each event. Suddenly, Rudolph was an international superstar. Foreign media outlets gave her nicknames such as “Queen of the Olympics,” “Black Pearl” and “Black Gazelle.” On a tour of Europe following the Olympics, Rudolph drew crowds everywhere she went. In Germany, admirers mobbed her bus. She couldn’t set any personal items down while in public for fear they would be snatched up as souvenirs.

Rudolph received a hero’s welcome when she returned to the United States, too. One of her stops was at the White House to meet President John F. Kennedy and Vice President Lyndon Johnson. In his book, Temple recounted this story about the meeting: “When President Kennedy came into the room he was so entranced meeting Rudolph that he missed his rocking chair when he went to sit down! We wanted to laugh when we saw that he wasn’t hurt, but we were trying to keep from it – he started laughing so we all joined in.”

In the book, Temple confided that he thought at the time he thought he had reached the pinnacle of his career and considered retirement. But in the 2015 interview, he also acknowledged that he got some disappointing news after returning from Rome: His successes as a coach hadn’t convinced the TSU administration to give him a pay raise or a bonus of any sort.

“I guess that hurt me more than anything else in the world,” Temple said. “(TSU) was a good place because you weren’t going to get the big head.”

Temple’s career as an Olympic coach wasn’t over yet, anyway. In four years, he returned as head coach with emerging stars Wyomia Tyus and Edith McGuire Duvall.

‘My hardest experience and my greatest experience’

A & I State University. Front: Summer school participant, and Martha Hudson. Back: Willie B. White, Coach Edward S. Temple, Wilma Rudolph and Darlene Scott.

Tyus, who had endured Temple’s summer training program as a high school student, accepted an offer to attend TSU on a work-study program because she saw that as the only realistic chance she had of attending college.

While many Tigerbelles worked with Temple in the university post office, Tyus took a job elsewhere on campus.

“Seeing him at the track was enough,” Tyus joked. But Tyus’ father had passed away not long before she started college, so Temple helped fill a void in her life.

“He became a father figure to me,” Tyus said. “He grew on me.”

Early in her career, Tyus admitted, she didn’t have the best form. Her stiff movements while running earned her the nickname “the mechanical machine.” After those issues were corrected, she became a world class runner.

Duvall had followed a similar path. She was planning to get a summer job rather than accept Temple’s offer to participate in his training program, but her high school coaches changed her mind. When she was ready for college, she also chose to attend TSU. And like Tyus, she described Temple as being a father figure.

“We always thought he was much older, even though he was only in his 30s then,” Duvall said.

Tyus and Duvall both qualified for the 1964 Olympic Games in Tokyo. They were joined by Temple, who had agreed to serve as head coach – albeit much more reluctantly than he had four years before.

Temple didn’t think it would be possible to top the team’s performance in the 1960 Olympics. His wife, Charlie B., convinced him to give it another try. “I didn’t think we could do any better,” Temple said candidly.

After arriving in Tokyo in 1964, Temple said his team’s preparations were complicated by disputes with the U.S. men’s team over equipment. The women’s team was supposed to get some of the starting blocks provided by the U.S. Olympic officials and passed down from the men’s team. However, Temple said the men’s team wasn’t willing to share the blocks, leaving the women to borrow blocks from other countries during practice. Temple said that put his athletes at a disadvantage because it’s helpful to practice with the same equipment that will be used in competition. As an added insult, Temple said the men’s team wouldn’t loan a sweat suit for his shot putter.

Despite the behind-the-scenes drama, there were high expectations for Temple’s Tigerbelles. Some were comparing Duvall to Wilma Rudolph and projecting that she would win three gold medals.

Both Duvall and Tyus said Temple helped take the pressure off of them. When Duvall started to withdraw into her shell in Tokyo, she said Temple encouraged her to “get out and socialize.” He told Tyus that not much was expected of her because she was so young.

“I went in it just to have fun,” Tyus said. “I thought of it as a party.”

It did become a celebratory atmosphere when Tyus and Duvall finished first and second, respectively, in the 100-meter dash. “I couldn’t believe it,” Temple said. “I was ready to pack up and go home.”

Duvall wasn’t quite ready, though. Seeking redemption after her silver medal performance in the 100-meter dash, she won the gold medal in the 200-meter dash. She, Tyus and former Tigerbelle Willye B. White also took home silver medals as part of the 400-meter relay team.

Looking back on the team’s successes and the headaches that had preceded them in the 1964 Olympics, Temple said “it may have been my hardest experience and my greatest experience.”

Paying the bills

Back at home, Temple was growing weary of keeping the TSU track program going with limited resources. Dwight Lewis, the longtime journalist for The Tennessean, said the program wasn’t financially self-sustaining even in its heyday.

“Track wasn’t bringing in any real revenue,” Lewis said. “It was bringing in publicity, but not money.”

Or, as Temple himself put it: “Fame don’t pay no bills.”

Faced with that reality, Temple said he considered walking away from the program. Fred Russell, a longtime sports writer and editor for the Nashville Banner, persuaded him to make a direct appeal to then-Governor Buford Ellington. Ellington, who had once supported segregation, agreed to recommend a bigger budget and athletic scholarships for TSU’s track program.

Although Temple got what he wanted, bypassing TSU’s administration and going directly to the governor’s office didn’t make him particularly popular with the school’s president or athletic director.

“I came back to the campus and I don’t think they spoke to me for half a year,” Temple said.

Although Temple didn’t return as coach of the 1968 Olympic team, Tyus won two more gold medals – one in the 100-meter dash and the other as part of the 400-meter relay team. Fellow Tigerbelle Madeline Manning also won a gold medal that year in the 800-meter race.

Temple’s teams continued to win national championships, compete in international competitions, collect medals in the Pan American Games and set numerous individual American and world records throughout the 1960s and 1970s. In 1972, Tigerbelle Madeline Manning earned a silver medal as part of the 4 x 400-meter relay team and then Tigerbelle Kathy McMillan won a silver medal in the long jump in the 1976 Olympics.

F.M. Williams, a journalist with The Tennessean, launched a campaign in the 1970s to raise money for the Edward Stanley Temple Track on the TSU campus. Dr. Roy Nicks, then-chancellor of the Tennessee Board of Regents, spearheaded an effort to provide public funds to supplement the private contributions.

Temple credited Williams, Nicks, Russell and Ellington for being among those who supported the program when they didn’t have anything to gain.

“They did it quietly,” Temple said. “There wasn’t any fanfare. They did it when it wasn’t popular.”

‘Success draws success’

A & I State University, now Tennessee State University.

Temple was scheduled for a third stint as Olympic coach in 1980 but the U.S. boycott of the Moscow Olympics derailed those plans.

Temple continued to coach the Tigerbelles until 1994 when he retired and was replaced by Chandra Cheeseborough, one of his star athletes from the late 1970s. Cheeseborough won the last three Olympic medals during Temple’s tenure in 1984, with gold medals as part of the 4 x 100-meter and 4 x 400-meter relay teams and a silver in the 400-meter dash. At this writing, she has served as the team’s coach for more than 20 years.

Temple credits Title IX, federal legislation aimed at preventing gender discrimination, with dramatically increasing the amount of money available for women’s college athletic programs. While that has made running a program easier, Temple said he noticed that the athletes he coached at the end of his tenure were less willing to endure the type of rigorous training and strict adherence to rules that made his earlier teams so successful.

Temple had a simple answer for maintaining a successful program over a long period of time: “Success draws success,” he said. For that reason, he professed to be an admirer of Geno Auriemma, head coach of the University of Connecticut women’s basketball team, whose lengthy career has included 10 national championships and five undefeated seasons through 2015.

After his retirement, Temple said he stopped attending practices and only rarely attends meets. He doesn’t feel compelled to give Cheeseborough, his former protégé, advice on how she should coach, either.

“After I retired, that was it,” Temple said. “I spent 44 years there. That was enough.”

Temple still attends university functions and works out twice a week at the YMCA in downtown Nashville, keeping fit by walking in the pool. He visits with his children and stops by his office and the special collections rooms at the campus library. In retirement, he said, “I do what I want to do and I do that slowly.”

Gone but not forgotten

More than 20 years after his retirement, Temple’s legacy still endures. He’s been inducted into the National Track Hall of Fame, the Tennessee Sports Hall of Fame, the Helms Hall of Fame, the Tennessee State University Hall of Fame, the Harrisburg (Pennsylvania) Central Area Chapter Hall of Fame, the Pennsylvania Sports Hall of Fame, the Ohio Valley Conference Hall of Fame, the Black Athletes Hall of Fame, the Communiplex National Sports Hall of Fame and the United States Olympic Hall of Fame.

The latter honor, which he received in 2012, was particularly meaningful to him. He’s one of only a handful of Olympic coaches inducted and he wished his wife, who passed away in 2008, had been there to share the experience with him.

“I just thought they had passed me by,” Temple said. “It was just one of those things.”

In late spring of 2015, preparations were being made to put a statue of Temple outside First Tennessee Park, the brand new home of the Nashville Sounds minor league baseball team located a short drive from TSU’s main campus.

Bo Roberts, managing partner and owner of Roberts Strategies, met Temple when both were serving on the Nashville Sports Council and quickly became an “Ed Temple groupie.” He spearheaded the effort to have the statue located at the baseball stadium.

Roberts said that in addition to being a great coach, Temple puts other people ahead of himself. For example, when the Nashville Sports Council was considering Temple for a lifetime achievement award, he asked that Fred Russell, the longtime Nashville Banner journalist who was ill at the time, be honored first.

“That’s the kind of person he is,” Roberts said of Temple.

Temple continues to have close relationships with his former Tigerbelles. They frequently come back to visit him when they are in town for various functions at the school. Wyomia Tyus and Edith McGuire Duvall said Temple’s humor has become easier to appreciate during those meetings than it was when he was a coach making wisecracks at their expense.

“He’s really a funny person,” Tyus said. “He’s just someone I could be around a long time and not be bored.”

Duvall agreed: “He was not funny then (as a coach). He was all business. We have a different relationship with him now than when we were running.”

After graduating from TSU, Duvall had a long career as a teacher, government employee and restaurateur before her retirement.

Duvall said Temple did more than coach track – he helped his athletes get the kind of education and life skills training they needed to succeed in life.

“To me, to put up with all those girls and their different personalities, he was an extraordinary man,” Duvall said. “We love Coach Temple. He had a lot to do with who I am today.”