As a photographer for the United States Army Corps of Engineers, Westcott was the only person allowed to have a camera in Oak Ridge while the Manhattan Project was under way in the 1940s. He took thousands of photographs of Oak Ridge residents at work and at play. When those photographs were eventually declassified, they became essential viewing for anyone hoping to understand the town and its role in history.

Ed Westcott Shared the Secrets of the Secret City

by Blake Fontenay

July 25, 2016

“Ed’s photographs fill a huge hole in the record that would have existed if not for Ed and his talent…It was one man capturing the history of a city of 75,000 people.”

David Bradshaw, former mayor of Oak Ridge from 2001 to 2007.

Ed Westcott Shared the Secrets of the Secret City

It all began, according to legend, with the bizarre ramblings of a local eccentric.

John Hendrix emerged from the East Tennessee woods after a 40-day walkabout, claiming to have had a vision.

“Bear Creek Valley someday will be filled with great buildings and factories,” Hendrix reportedly told anyone who would pay attention to him. “Thousands of people will be running to and fro. They will be building things, and there will be great noise and confusion and the earth will shake. I’ve seen it. It’s coming.”

At the time, people put little stock in Hendrix’s words. The area he described was a lightly-populated farming area west of Knoxville. But nearly three decades after his death, the land was transformed into what is now the city of Oak Ridge.

Behind gates and fences patrolled by armed guards, thousands of people in Oak Ridge worked on a process for refining the radioactive material that would be used in two atomic bombs. When they weren’t helping to create the weapons that would end World War II and dramatically change the course of world history, the town’s residents busied themselves with the minutia of everyday life: grocery shopping, swimming, attending church services, baseball games, dances and movies.

At its heyday in 1945, Oak Ridge had 75,000 residents, making it the fifth largest city in Tennessee at the time. Yet because their work was shrouded in secrecy, much of Oak Ridge’s early history would remain unknown - if not for a man named James Edward “Ed” Westcott Sr.

As a photographer for the United States Army Corps of Engineers, Westcott was the only person allowed to have a camera in Oak Ridge while the Manhattan Project was under way in the 1940s. He took thousands of photographs of Oak Ridge residents at work and at play. When those photographs were eventually declassified, they became essential viewing for anyone hoping to understand the town and its role in history.

“We wouldn’t know how it evolved because of the classified nature of the project, if Ed hadn’t been here,” said David Bradshaw, who served as the town’s mayor from 2001 to 2007. “Ed’s photographs fill a huge hole in the record that would have existed if not for Ed and his talent…It was one man capturing the history of a city of 75,000 people.”

Shoe Displays and FDR

Born in Chattanooga and raised in Nashville, Westcott developed an interest in photography at an early age. Don Hunnicutt, Westcott’s son-in-law, said both of Westcott’s parents helped cultivate that interest.

“His mother was a big influence on him as far as getting him interested in photography,” said Hunnicutt, who has served as an unofficial spokesman since Westcott’s speech was impaired by a stroke several years ago.

Westcott was 13 when his father bought him a French-made Froth Derby camera. Westcott took to what would eventually become his life’s work immediately. Before long, he was developing photographs for friends and neighbors in a makeshift darkroom he created out of an old pie wagon in his backyard.

In the early years, Westcott was mostly self-taught.

It didn’t take long before his budding interest landed him a big photographic scoop. At age 14, Westcott learned that President Franklin Delano Roosevelt would be traveling through Nashville’s Centennial Park in his motorcade. Westcott managed to worm his way through the crowd to get a shot of the president.

Even at that young age, “he pretty much knew the ins and outs of how to get around,” Hunnicutt said. “With a camera, you can pretty much get places that most people can’t.”

As it turned out, Roosevelt was one of several presidents Westcott would photograph during his career.

After graduating from Andrews High School, Westcott began more formal training in his craft. He attended the Watkins Art School in Nashville, then did an internship with the National Youth Administration and worked for the Photo Craft Studio and Shadow Art Studio, also in Nashville.

His early assignments as a studio photographer were fairly commonplace – weddings and other family functions were a staple. Hunnicutt said one of Westcott’s early studio projects involved a photo essay on the business of selling shoes.

“As time went on and he gained experience, they could see his talent was above the normal,” Hunnicutt said. “He was sent on different assignments with more importance.”

A Choice Between Tennessee or Alaska

Westcott had just turned 20 when he made the life-changing decision to go to work in the Corps of Engineers’ Nashville field office. He was assigned to photograph federal projects and installations in seven southeastern states. These included military bases, hydroelectric plants, flood control locks and a planned prisoner of war camp in Crossville.

Westcott had only been working in the Nashville office for less than a year when he found out the office would be closing and he was forced to make a pivotal decision which he later described in an interview recorded in 1999 for the Center for Oak Ridge Oral History.

“There was a recruiting officer (who) came and talked to a number of people about coming to a job near Knoxville, Tennessee and also one on the Alaskan Highway – and they needed a photographer in both places,” Westcott said in the interview. “I said I’d like to go to Knoxville because I’m familiar with East Tennessee because I’d been up here on assignments for the government before.”

His official title was chief photographer for the Manhattan Engineering District, Clinton Engineer Works. Westcott didn’t know exactly what his new job entailed. And when he arrived, there wasn’t very much to photograph.

“They had an old garage showroom and a repair shop there,” Westcott said of the Knoxville headquarters. “That’s where the first office was set up. And we worked out of that, coming to the site (of future Oak Ridge) daily, so that’s what brought me here. That was December of 1942. They had just broken ground that October, started some railroad work into Oak Ridge and things of that nature, but other than that there was very little going on except preliminary grading and surveying.”

‘Secret City’ Sprouts Up Almost Overnight

The preliminary work Westcott saw upon his arrival actually predated Roosevelt’s official approval of the Manhattan Project. That didn’t come until Dec. 28, 1942, according to The Manhattan Project: The Making of the Atomic Bomb, a book produced in 2001 by the U.S. Department of Energy.

By that time, as Westcott noted upon his arrival, development of the project was already in its early stages.

The United States Army had already acquired 59,000 acres of property, requiring the relocation of about 3,000 rural residents.

The Army’s initial plans for the site called for about 13,000 people to live and work in the area. There were plans to house them in prefabricated homes, trailers and dormitories and use buses to ship them to three production facilities built in valleys outside town.

The scope of the project quickly expanded, both in terms of production facilities and number of workers needed. According to the Department of Energy’s book, there were 75,000 people living in Oak Ridge by September of 1945 and the production facilities were so large that they were consuming one-seventh of the nation’s total energy production.

Despite all the activity, few in the outside world knew much about what was happening in Oak Ridge.

Don Hunnicutt, Westcott’s son-in-law, said growth was happening along Oak Ridge’s muddy streets so fast that it was difficult to keep up with it all.

“They put people everywhere they could,” Hunnicutt said. “Housing was built so fast that when kids went to school in the morning and they came back (in the afternoon), they wouldn’t recognize where their house was.”

With the war raging, supplies – everything from groceries to gasoline to tires to cigarettes – all were rationed. Hunnicutt said if people saw a line forming, they would quickly join it to make sure they weren’t missing out on something they might need.

“Standing in line was just common,” Hunnicutt said.

Westcott’s job was to document it all, from the work with high-tech machinery to how workers and their families were filling their off-hours. The project’s engineers directed him on what to photograph on the technical side of the uranium enrichment process. Westcott was left to his own initiative to capture slices of everyday life.

He developed most of the photos himself and kept them in storage, unless the Corps of Engineers requested them. Some of them were used in the Oak Ridge Journal, the local newspaper operated by the Army but forbidden to be taken outside the city’s walls.

He photographed rows of women monitoring the control panels of enormous machines called calutrons. He photographed people overseeing the transformation of silver bars into magnetic coils. He photographed shift workers heading home for the day.

Some of his images were lighthearted, like those of children playing or the three bathing suit-clad women at the swimming pool that Westcott would later jokingly characterize as “one of the toughest assignments he ever had.”

His job could be very stressful, though. The Corps of Engineers was very particular about the types of facilities and activities Westcott needed to document and some areas were off limits even to his camera. Film during that era contained silver, a material that was much in demand as part of the war effort. For that reason, Hunnicutt said Westcott had to make his shots count.

The Secret City Lives Up to Its Nickname

Like most people living in Oak Ridge, Westcott didn’t know exactly what the Manhattan Project involved. Workers knew what their own job responsibilities were, but very few had a complete picture of the overall mission. Hunnicutt said his father-in-law probably developed some suspicions over time.

“As time went on and he photographed a lot of things, he kind of got an idea by getting a physics book and reading a little of the physics book, and kind of putting two and two together, but he wasn’t really sure exactly what was going on,” Hunnicutt said.

Secrecy was on everyone’s minds. Signs were posted throughout the community, urging people to keep quiet about their work. Rallies were periodically held to reinforce the same message. Westcott photographed billboards urging residents to “keep mum about this job” and “guard your talk.” Westcott recalls one of his favorite photographs of a war bond rally being cropped to exclude one of the larger operating facilities Army officials wanted to keep secret from the outside world.

One of his Christmastime photos even shows a man dressed in a Santa Claus suit being searched at a security checkpoint.

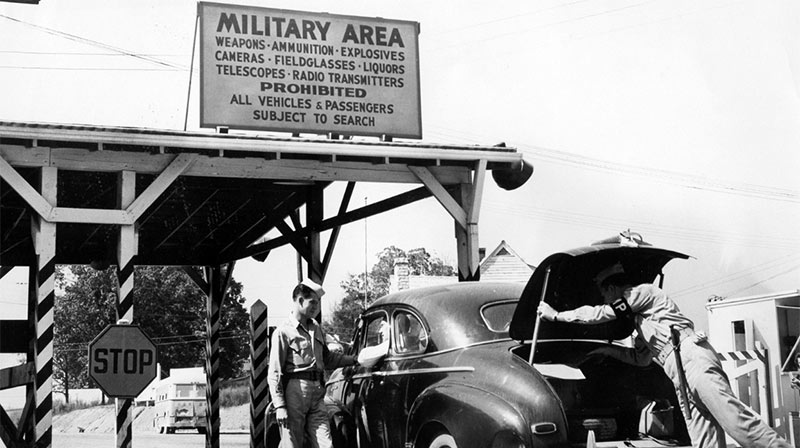

Since cameras were banned from Oak Ridge, Westcott frequently had to show his credentials to the guards.

“There were a lot of FBI people here,” Hunnicutt said. “Also, they recruited some of the residents of Oak Ridge to be what you might call undercover spies, that if they saw or heard anything that was out of what they had been taught not to say, they were supposed to turn those people in and they would be questioned. There were numerous accounts of people relating stories about people waiting to be hired and a man says ‘I know what they’re making out here,’ such and such, and somebody comes in and gets him and they never see him again. A guy was working a crossword puzzle on a bus and he said ‘Hey, buddy, what’s the symbol for uranium?’ When he got off the bus, he was escorted to a room and they wanted to know why (he had asked). The word ‘uranium’ was absolutely top secret. You didn’t say that.”

The Atomic Bomb’s Legacy in Oak Ridge

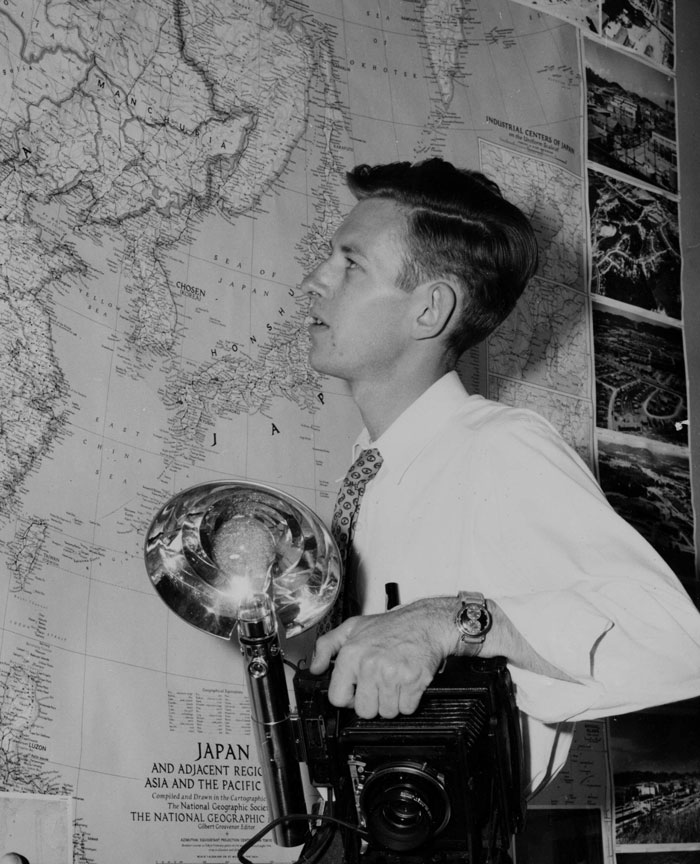

In hindsight, one of the most hair-raising photos Westcott took depicted Leslie R. Groves, the Army general who was overseeing the Manhattan Project, in the summer of 1945. Westcott was summoned to Groves’ office in Washington, D.C. and asked to get a photograph of the general looking at a map of Japan. As a way of staging the photograph, Westcott suggested that maybe Groves wanted to focus his attention on Tokyo, which had recently been firebombed by Allied forces. Groves refused, saying he was looking “somewhere else.”

Westcott later realized that Groves was staring at Hiroshima, which would soon be the target of the first atomic bomb dropped on Japan.

After the bombs had been dropped, the Army sent planes over Hiroshima and Nagasaki to take photographs of the devastation. Those photographs were taken to Westcott’s photo lab in Oak Ridge, where they were developed as armed guards waited in the hallway.

Westcott therefore became one of the first people other than those who had witnessed the destruction firsthand to see the power the Atomic Age had unleashed. Those photos showed, aside from a few buildings that somehow survived the blasts, two major cities that had been reduced completely to rubble.

“Even today, if you look at those photographs, it’s hard to imagine,” Hunnicutt said. “Because you’ve seen photographs of tornadoes coming through and hurricanes. This is just multiplied more than those.”

Like many who have lived in Oak Ridge, Hunnicutt said Westcott had mixed feelings about the Manhattan Project’s results.

“Some people were joyful because their brothers or fathers or someone was in the military and they didn’t have to invade Japan,” Hunnicutt said. “Others were sad because of the devastation and the lives lost. But if you think about it, the spinoff of the nuclear medicine from the atomic energy it produced and how everything was made – there’s a lot of people today who are alive because of the medical spinoff from it.”

Those aerial photos Westcott developed from the bombing sites were used with news releases the Army sent out across the country and around the world.

Japan surrendered on Aug. 15, 1945. Oak Ridge residents had begun to gather in the Jackson Square shopping center when rumors about the war’s impending end spread throughout the community.

Westcott climbed atop a flatbed truck and photographed the celebrating masses, several of whom held up newspapers proclaiming “War Ends” in type covering the top half of the front pages. That image became one of the war’s iconic photos that was also shared in media outlets around the world.

Giving Orders to Presidents

After World War II ended, the United States Atomic Energy Commission was formed to oversee continued research and development work at Oak Ridge. Westcott remained on the job as the commission’s chief photographer.

In that capacity, he started a photo archives that has been continued by his successors. He continued to photograph construction and operations of atomic and nuclear installations across the country. He managed photographic activities for underground nuclear weapons tests near Hattiesburg, Mississippi.

“If it was necessary, he went,” Hunnicutt said. “I think the adventure of not knowing what you were going to photograph made it exciting.”

In 1966, he transferred to the Atomic Energy Commission’s headquarters in Germantown, Maryland. In his 1999 interview with the Center for Oak Ridge Oral History, he joked that “I must have done something wrong because they transferred me to headquarters in Washington.”

His new assignment was hardly a punishment, though. Westcott was responsible for documenting the commission’s activities in Washington, which included photographing events attended by Lyndon Johnson, Richard Nixon, Gerald Ford, Jimmy Carter, Ronald Reagan, George H.W. Bush and John F. Kennedy, most of them while serving their terms as president. He also photographed many other high-ranking U.S. and foreign officials during his time in Washington.

D. Ray Smith, a historian who writes the “Historically Speaking” column for The Oak Ridger, described Westcott’s ‘take charge’ approach to photographing famous people in a note Westcott wrote to one of his assistants.

“You are doing them a favor and you have the right to direct them toward making a better picture,” Westcott wrote. “You hold the camera and they are here for you as a favor to them. They will do anything you say, so don’t be afraid to say it. You are free to order them around because the camera is like a gun.”

Of the presidents he photographed, Hunnicutt said Westcott’s favorite was Carter because of his politeness and easygoing nature. Westcott’s work appeared in everything from textbooks to newspapers to museum exhibits. He also shot video, which appeared in movies and television programs. He received numerous awards from the Department of Energy and the Atomic Energy Commission throughout his career.

A Highly Experienced Darkroom Assistant

Westcott officially retired in 1977, although he didn’t slow down much. He and his wife, Esther Seigenthaler Westcott, returned to Oak Ridge, where he continued to photograph scenes of everyday life, just as he had during the war. One of his projects involved photographing the former home and gravesite of John Hendrix, the man who had prophesied about the rise of Oak Ridge decades before the Manhattan Project.

He also assisted his successors at the Department of Energy in Oak Ridge. Lynn Freeny, who took photographs for the Department of Energy as a private contractor, recalls starting work there in the late 1980s with a darkroom assistant who seemed unusually knowledgeable for someone in that position. It was Westcott.

“I didn’t know who this guy was,” Freeny said. He quickly learned, though, and developed an immense respect for Westcott’s work.

“He could pose people in ways that didn’t look like they were posed,” Freeny said. “I could never do that.”

Freeny said Westcott took great pride in his work and created photos with an artist’s touch, which explains why so many of them are so admired.

Westcott has always been friendly and approachable, Freeny said, never taking on the persona of a big-time photographer. Westcott does, however, show off his sense of humor from time to time.

Freeny recalls one instance where Westcott rigged two boards, a pair of pants and a pair of boots to make it appear as though two legs were sticking out of the ground at a local cemetery. Westcott just wanted to see how people passing by would react.

Mick Wiest, president and chief executive officer of the Oak Ridge Heritage and Preservation Association, said age didn’t slow Westcott much.

“Even when he was in his late 80s, he would climb ladders to get shots of people,” Wiest said.

Westcott’s photographs can be found on display in many businesses around Oak Ridge. The American Museum of Science and Energy, which is located in Oak Ridge, has an Oak Ridge history room that is filled with Westcott’s photos.

Ken Mayes, the museum’s deputy director, said some of those photos were used to prepare a traveling exhibit featuring Westcott’s work.

Some of the work on the Manhattan Project occurred at facilities located in Los Alamos, New Mexico and Hanford, Washington. However, Mayes said those cities don’t have a comparable photographic record from that era because they didn’t have Ed Westcott working there.

“He’s a photographer at heart,” Mayes said. “Until recently, I always saw him with a camera in his hand. He loved what he did and I think that shined through in the work that he did.”

Getting Recognition Late in Life

While Westcott spent most of his career behind the scenes, his reputation since his retirement has grown tremendously.

Although his health has declined in recent years, he continues to attend many community events and remains very visible in the community.

Phil Westcott, Ed Westcott’s grandson, recalls one time the pair went to a cafe and found it difficult to carry on a conversation because they were interrupted so often by friends and well-wishers.

“He means so much to the community,” Phil Westcott said. “It’s very humbling, but it teaches me not to take anything for granted.”

In the early 2000s, Oak Ridge held Ed Westcott Day. Bobbie Martin, a charter member of the Oak Ridge Heritage and Preservation Association, said Westcott received a proclamation from the mayor and an exhibit at the museum was dedicated in his honor on that date.

Since then, the accolades have continued to pile up. He received a key to the city in 2008. That same year, one of the main roads in a new housing development was named Ed Westcott Boulevard.

State legislators got into the act in 2012, passing a resolution in honor of his 90th birthday. In 2014, a shopping center was named The Westcott Center. Employees of the center’s Kroger store voted to bestow that honor on Westcott.

Also, Westcott fulfilled one of his dreams in 2005 when he was able to publish many of his favorite photographs in a book titled, Oak Ridge, which was part of the “Images of America” series.

Westcott also pursued some of his other hobbies in retirement, which include ham radio and water divining. He’s also helped out with photography projects at local elementary schools.

The stroke that he suffered in 2005 left him unable to write with his right hand. D. Ray Smith, the Oak Ridge historian, said Westcott taught himself how to write left-handed, allowing him to continue to autograph copies of his book.

Appreciating the Historical Nature of His Work

Phil Westcott, Ed Westcott’s grandson, also got into the photography business. However, the younger Westcott said no one in the family pressured him to follow in his grandfather’s footsteps.

“There was some encouragement there, but it was never pushed on me,” Phil Westcott said. “It came very naturally. That’s not to say they weren’t immensely supportive when I did show an interest.”

Although he primarily works on digital photo editing now, he’s been a nature photographer for land management agencies at different points in his career.

Phil Westcott said his grandfather tried to teach him about film development at a young age, “whether I liked it or not or whether I paid attention or not.”

But Phil Westcott said his grandfather only saw the technical side of photography as a means to an end.

“He has such a great understanding technically, but the objective was always to communicate,” Phil Westcott said.

And Phil Westcott said his grandfather shared many of his photos. When he talked about them, the emphasis was always what was in the photo – not who was on the other side of the camera or whatever trouble it might have taken to get that particular photo.

Phil Westcott said his grandfather had a great respect for the historical nature of his work, including the Manhattan Project and the impact it had on the whole world.

Oak Ridge through Ed Westcott's lens

Ed Westcott

Born: January 20, 1922

Education: Watkins Art School

Career: Photographer for U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission

Notably:

- As a photographer for the United States Army Corps of Engineers, Westcott was the only person allowed to have a camera in Oak Ridge while the Manhattan Project was under way in the 1940s.

- Westcott was responsible for documenting the commission’s activities in Washington, which included photographing events attended by Lyndon Johnson, Richard Nixon, Gerald Ford, Jimmy Carter, Ronald Reagan, George H.W. Bush and John F. Kennedy, most of them while serving their terms as president.