A newspaper once dubbed John Jay Hooker Jr. as “Tennessee’s own Kennedy.” And the label seemed to fit. The one-time aide to Robert F. Kennedy made a name for himself during his campaigns for Tennessee governor in 1966 and 1970. Although he wasn’t successful in either of those campaigns – or others that followed – he has remained part of the state’s political landscape for more than a half century. A lawyer by trade, he’s also tried his hand with varying degrees of success as a restaurateur, a publisher and a health care executive. As former Governor Winfield Dunn, the man who beat Hooker in the 1970 election, put it: “When people run out of things to talk about, they talk about John Jay Hooker.”

John Jay Hooker, Jr. – When It Came to Tennessee’s Political Wars, He’d Always Volunteer

Heading down the homestretch of his campaign for Tennessee governor in 1970, John Jay Hooker Jr. had a lot of reasons to play it safe. He had managed to beat out the Democratic Party’s establishment candidate in the primary – a feat that had eluded him four years before. All he had to do was run a low-key campaign and count on partisan support in a state that hadn’t elected a Republican governor in half a century.

But Hooker, a descendant of one of Tennessee’s founding fathers, wasn’t the kind of person who liked to play it safe. On the campaign trail, he was outspoken in his support of the Civil Rights Movement and in his opposition to the Vietnam War – both among the most divisive issues of the 1960s and early 1970s.

A lunchtime speech Hooker gave to a group of Nashville businessmen 28 days before the 1970 election was emblematic of his approach to campaigning. At a time when war protests were rocking college campuses and dominating the news, Hooker had sharp words for his Republican opponent, Winfield Dunn, whom he suggested would take a far tougher approach toward the protestors than he thought was warranted.

“I’ve come to tell you that the Democratic Party has a standard bearer who is going to extend the hand of friendship to all the citizens of this state,” Hooker said in his deep booming voice. “The truth about it is the children on the college campuses in this state are our children. What we need is a governor who will extend the hand of friendship. The Republican nominee is talking about being a two-fisted governor. I’m talking about (being) a governor who will go out and see the people on the college campuses and every place else, give them the opportunity to be heard and understood.”

It was just one of many campaign speeches that Hooker gave that year, but it illustrated many of the traits he would demonstrate again and again over his long political career: Strong oratory skills. Unwavering belief in his principles and absolute certainty about how to best live them out. And a willingness to directly confront his foes, even in situations where diplomacy and pragmatism might have served him better.

Hooker’s opponent Dunn ended up winning the 1970 election in a race that Dunn said, in an interview 45 years later, “was more about personalities than anything else.”

“We had an interesting campaign, to say the least,” said Dunn, who didn’t have a fond impression of Hooker at the time, although they’ve since become close friends.

The 1970 election turned out to be a pivotal moment in the career of Hooker, who had close ties to the politically powerful Kennedy family. Had he been elected governor, Hooker said in a 2015 interview that he felt confident that he could have used that position as a springboard to successfully run for president someday. Instead of Georgia governor Jimmy Carter and his wife Rosalynn winning over the nation’s voters with their Southern charm in 1976, Hooker said he envisioned himself and his then-wife Tish in that role.

“I’ll go to my grave believing Tish and I would have beaten Jimmy and Rosalynn,” Hooker said.

His loss in 1970 was followed by other electoral defeats, yet he has remained a player in Tennessee’s political and legal arenas throughout the years. Along the way, he also met and befriended celebrities and made and lost millions of dollars on an assortment of business ventures. Hooker expressed few regrets over the way his career and his life have played out.

Living Like a Republican, Voting Like a Democrat

Hooker was born into a life of privilege. His father, John Jay Hooker Sr., was a highly-regarded attorney. The family lived in the wealthy Nashville suburb of Belle Meade, with a home maintained by servants whom the younger Hooker considered to be “authority figures.”

The son developed an admiration for his father’s career at an early age, as well as his political leanings. Many years later in that 1970 campaign speech, Hooker quipped that when he was six years old, his father expressed hope that even if he ended up “living like a Republican, he’d have sense enough to vote like a Democrat.”

A couple of years later, Hooker Jr. developed his earliest political ambitions after seeing a newspaper headline about his father’s decision not to run for governor. It was at that moment that Hooker Jr. knew that he himself wanted to run for governor someday.

“At the time, I didn’t know, at eight years old, anything about the concept of winning and losing,” he said. “I just knew I was going to try, to give it my best effort.”

Hooker Jr. graduated from Nashville’s Montgomery Bell Academy and attended the University of the South in Sewanee before serving as an investigator in the U.S. Army’s Judge Advocate General’s office. Following his stint in the service, he earned a law degree from Vanderbilt University.

At Vanderbilt, Hooker was part of the Class of 1957, which became renowned for the number of its graduates who went on to accomplish great things in their careers. The class included Jim Neal, a Watergate prosecutor who also successfully tried Jimmy Hoffa for jury tampering, George Barrett, a civil rights and labor lawyer, and Tom Higgins, an insurance attorney who became a federal judge.

In a 2002 Nashville Scene article about the Class of 1957, Hooker recalled being less excited about law school than some of his classmates.

“I was not a very good student,” Hooker said, noting that he graduated last in his class. “I didn’t like law school. It didn’t interest me.”

Hooker did enjoy watching his father’s flamboyant performances in court, though.

“Higgins and Neal were very interested in the law in the abstract,” Hooker said in the Scene interview. “I was more interested in watching my dad try a lawsuit.”

In the same article, Barrett recalled Hooker’s study habits left a lot to be desired.

“We used to have study groups together, but John Jay would never come,” Barrett said. “He’d finally show up at the last minute and say, ‘tell me what I need to know.’ And so we all helped him.”

Hooker began his law career working for his father’s firm before founding a firm with his brother Henry. It wasn’t long before Hooker Jr. would get an opportunity to work on a case that would change his life.

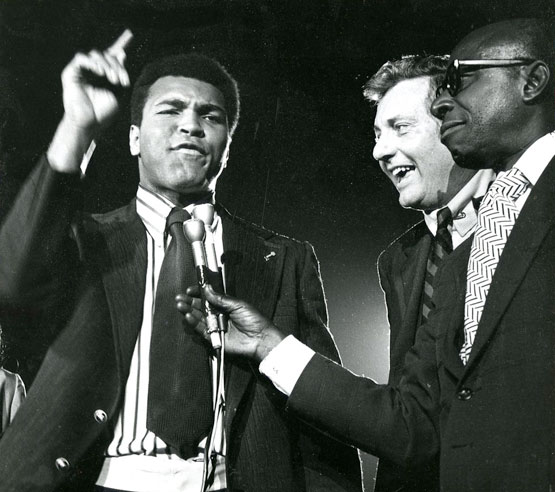

In Kennedy’s Inner Circle

One of Hooker’s first big breaks came in 1958, when Hooker became an assistant to Jack Norman Sr., one of the era’s legendary attorneys, in prosecuting the impeachment trial before the Tennessee State Senate of Raulston Schoolfield, a state judge from Chattanooga who was facing corruption charges.

“I was a lackey,” Hooker said. “I was on call 24 hours a day and basically did whatever Mr. Norman wanted me to do.”

At the time, Hooker said he thought he was chosen for the job strictly on merit. He later learned he had been selected so that his father would have a conflict of interest and therefore be ineligible to represent Schoolfield.

The trial generated a lot of publicity. Since Schoolfield was accused of taking bribes from the organized labor movement, it also attracted the attention of a U.S. Senate committee on which Robert F. Kennedy served as general counsel.

Kennedy was called as a witness in the impeachment proceedings. Afterward, Hooker took Kennedy to see the Hermitage, Andrew Jackson’s home, and put him up for the night after he missed his flight home. It was the beginning of a friendship that lasted throughout Kennedy’s life.

Hooker and his mentor Norman won the case – and Hooker also made important contacts that would serve him well throughout his professional career.

When Kennedy’s brother John ran for president, Hooker campaigned for him along with John Seigenthaler, who had covered the Schoolfield trial for The Tennessean and would become another longtime political ally of Hooker’s.

When John F. Kennedy was elected president and appointed Robert F. Kennedy as his attorney general, Hooker was hired as Robert Kennedy’s special assistant. No mere employee, Hooker lived in the Kennedy’s home and dined with the family.

Hooker worked on various special projects for Kennedy, including reviewing “thousands of pages” in files about Jimmy Hoffa, the Teamsters union leader. By then, the personal enmity between Kennedy and Hoffa was well known.

Yet Hooker, then only 31, took a contrarian position to that of Kennedy’s other advisers in recommending against prosecution of Hoffa. Hooker said that he felt like the evidence of Hoffa’s involvement in corruption was too thin and that Kennedy’s efforts would be perceived as a personal vendetta.

Kennedy decided to move forward with the prosecution, anyway. Kennedy did follow Hooker’s recommendation to hire Vanderbilt Class of 1957 alumnus James Neal take the lead in the case. Nevertheless, Hooker said his differences of opinion with Kennedy over the case led to awkward silences between the two men.

Hooker said he confronted Kennedy about getting the silent treatment. Kennedy eventually asked Hooker to recommend a replacement for himself, to which Hooker said he replied: “Bobby, you’ve got 32,000 lawyers around here. Get your own damn lawyer.”

Although their professional relationship ended, Hooker said he maintained his friendship with Kennedy and his family.

Teaming Up With The Tennessean

Hooker returned to Nashville to practice law, where he was reunited with John Seigenthaler, who had returned from his own stint in the Kennedy administration to The Tennessean’s newsroom. Hooker was hired as the newspaper’s general counsel – and he recommended that publisher Amon Carter Evans make Seigenthaler the newspaper’s editor in 1962.

The Tennessean crusaded relentlessly for causes its leaders believed in, including the Civil Rights Movement at a time when it was deeply unpopular in the South. The newspaper also exposed all manner of government corruption.

“We were tough,” Hooker said. “We thought the function of The Tennessean was to monitor the government. We thought it was our major responsibility.”

During those years, Hooker said Evans gave Seigenthaler and his staff a lot of editorial freedom. “Make no mistake, Amon owned the piano,” Hooker said, “but he let us play it.”

In 1966, Hooker decided to wage his first campaign for governor. He was opposed in the Democratic primary by Buford Ellington, who was seen as the party’s establishment candidate.

As usual, Hooker was counting on The Tennessean to support his bid – and it did. “I wouldn’t go to the bathroom without consulting them,” Hooker said of his newspaper allies. “We were a team.”

Ellington had formidable allies of his own backing his campaign, including sitting Governor Frank Clement and The Nashville Banner. Hooker held himself up as part of a new faction of the Democratic Party that aimed to change the status quo.

Hooker took well to life on the campaign trail. Hal Hardin, who volunteered to serve as the campaign’s bus driver and ended up serving as Hooker’s personal aide, characterizes the 1966 gubernatorial election as the “last hurrah” of old-style campaigning, where stump speeches at public appearances held more importance than they have in more modern campaigns.

Hardin said Hooker was greeted by large crowds at his campaign stops – and the candidate didn’t disappoint his supporters.

“It was like having The Beatles coming to town,” Hardin said. “Of course, he was an electrifying speaker.”

Hooker’s popularity was also boosted by a catchy campaign jingle that was well received around the state.

In a Aug. 1, 2002 article, The Nashville Post ranked Hooker’s matchup against Ellington as one of the best campaigns in the state’s history, referring to Hooker as “Tennessee’s own Kennedy.”

“If (Estes) Kefauver’s victory (in a 1948 U.S. Senate campaign) signaled the beginning of the end of the state Democratic Party’s old guard, then John Jay Hooker’s near miss in the 1966 gubernatorial primary was the old guard’s last hurrah. That Hooker, a Kennedy liberal, even considered taking on one-time segregationist Buford Ellington was considered an extremely bold move at the time.”

The article noted that even detractors turned out to hear Hooker’s speeches.

“We thought we were going to win,” Hooker said. “The reason we thought that was because we had these big crowds.”

Hooker had a plan to hedge his bets, though. In addition to running in the Democratic primary, he planned to register as a Republican. He figured that people who voted against Ellington in the primary would vote against him in the general election, as would Republicans.

However, to Hooker’s chagrin, the aide charged with registering him as a Republican candidate failed to do so before the deadline. So Hooker appeared only on the Democratic primary ballot.

When Ellington won the primary, Hooker said he was devastated. While Hooker believes his stance on the Civil Rights Movement earned him an overwhelming portion of the black vote in that primary, it cost him with white voters.

“We paid a price for that in the white community,” Hooker said. “We would have been better off if we had kept our mouths shut.”

A ‘Constructive’ Campaign Against Dunn

While Hooker was bitterly disappointed in his loss in the 1966 primary, it didn’t deter him from running again in 1970. Although his popular political jingles were back for his second campaign, he shifted his strategy somewhat.

During an interview with broadcast journalist Teddy Bart before the Democratic primary, Hooker talked about focusing less on stump speeches and more on one-on-one interaction with voters. He told Bart a major focus of his campaign was to improve education, thus making the state more attractive to new industry.

Tennessee needed to boost its share of the national per capita income to, in Hooker’s words, get “a bigger piece of the national pie.”

“The important thing for people to understand is that there is a competition and we are competing against 49 other states,” Hooker told Bart.

Hooker also said he was taking a “constructive” approach in his campaign rhetoric, an apparent pledge to run a positive campaign.

His strategy worked well enough in the primary election, when he beat a field of several candidates, earning him the right to face the Republican nominee Winfield Dunn in the general election.

Dunn, a Memphis dentist and Shelby County Republican Party activist, didn’t know much about Hooker before the race, but what he did know wasn’t very favorable. A friend of Dunn’s had pointed Hooker out to him at a social event at the Belle Meade Country Club two years before they met in the gubernatorial election. Dunn remembers seeing Hooker with his feet propped up on a table at the country club in a characteristically self-assured pose.

“I was hearing quite a few comments from Nashvillians that he was arrogant, that he could be heavy handed with other politicians and that he wasn’t someone who needed to be governor,” Dunn said.

During the campaign, though, Hooker tried to build a broad coalition of support by offering a centrist message.

In his 1970 lunchtime speech to the Nashville businessmen, Hooker said: “In 1964, a man ran for president of the United States – the Republican nominee – who said extremism in defense of liberty is no vice and that moderation in pursuit of justice is no virtue. In 1964, I thought that was wrong. In 1970, I think it’s wrong. What we’ve got to do is reject the extremism on either side, the right or the left. The simple truth is, gentlemen, that moderation is at the core of our society.”

However, while Hooker may have vowed to run a “constructive” campaign, that didn’t mean he shied away from controversial issues of the day, including the Civil Rights Movement and the Vietnam War.

At one point during the campaign, Hooker said he received a warning from Governor Ellington, his erstwhile foe, about a possible death threat. Ellington assigned plainclothes police officers to protect Hooker on the campaign trail.

Hooker said he knew speaking out about those hot button issues could cost him votes, but he didn’t care.

“It was who I was,” Hooker said. “The price of that was there were people in Tennessee who despised me.”

Dunn won the election, for a number of reasons. He built a winning coalition among Republicans, who had found a consensus candidate, and Democrats who had supported Hooker’s opponents in the primary. Hooker’s campaign was also hampered by an investigation by the federal Securities and Exchange Commission into one of his highest profile business ventures.

Becoming the ‘Pepsi’ to Kentucky Fried Chicken’s ‘Coke’

In the 1960s, Hooker had watched the growth of the Kentucky Fried Chicken restaurant chain and developed a business plan.

He teamed up with popular country music singer Minnie Pearl to launch a chain of fried chicken restaurants that were plainly designed to piggyback on Kentucky Fried Chicken’s success.

“I got into the chicken business on the premise that if Kentucky Fried Chicken was the Coca-Cola (of the restaurant industry), then we could be the Pepsi Cola,” Hooker said.

Minnie Pearl’s Fried Chicken began selling franchises and expanded quickly, causing the company’s stock prices to rise dramatically.

“John was at one time worth tens of millions of dollars,” said Aubrey Harwell, a Nashville attorney who has followed Hooker’s career. “It temporarily made John a multi-millionaire.”

However, the Securities and Exchange Commission launched its investigation over questions about how Minnie Pearl’s Fried Chicken was reporting the fees it received from franchisees.

When new franchises opened, the operators were required to pay a portion of the franchise fees they owed, with promises to pay the rest later. However, Hooker said the company followed the advice of its accounting firm, Price Waterhouse, which recommended reporting on its books the full amount of the fees – paid and unpaid – as income.

The Securities and Exchange Commission investigation focused on whether the company should have reported only the amounts already paid by franchisees.

The investigation lasted three years, causing what Hooker characterized as the company’s “strangulation.” Hooker said the federal agency instructed the company to keep its income information proprietary during that period, which scared away potential franchisees and investors.

Hooker had been involved in other business ventures at the time, including becoming one of the early investors in the Hospital Corporation of America, known as HCA. Hooker said the $1 million he invested in HCA stock quickly grew in value to $11.8 million within a nine-month period.

“We put every dollar of that into Minnie Pearl’s chicken,” Hooker said.

The Securities and Exchange Commission investigation concluded without any charges being filed against Hooker or Minnie Pearl’s Fried Chicken, but by then the financial and political damage had been done.

The chain was floundering financially, although it continued to operate for several years after the investigation ended. Hooker believes the investigation also played a big part in undermining his chances to win the 1970 gubernatorial election. Hooker said he’s convinced the investigation was politically motivated, launched at the behest of President Richard Nixon’s administration to aid Dunn’s campaign.

Hooker described the investigation of Minnie Pearl’s Fried Chicken as one of the most difficult times in his business career.

“Scores and scores of people thought I’d cooked the books,” Hooker said. “Losing the governor’s race was painful. Losing my money was painful. (But) losing my reputation as an honest man was truly painful.”

Hooker continued to dabble with other business investments, including a short-lived chain of hamburger restaurants. At one time, he talked about opening a Planet Nashville, with a concept mimicking the successful Planet Hollywood chain.

Hooker described his strength as a businessman as recognizing good concepts and providing the financial resources necessary for success. Yet he freely admitted that his strategy hasn’t always worked.

“I have not played flawless ball,” Hooker said of his business career. “I’ve made some big errors.”

He likened his business style to fishing:

“If you’re going to go fishing, go where the fish are. First of all, fish in the right pond. Second of all, fish with the right bait. Third of all, fish with the right people. What I’ve been good at is the conceptualization of a good idea.”

But even after two high profile but ultimately unsuccessful campaigns for governor, Hooker wasn’t resigning himself to private life. His political career was not yet over.

Cocktail Campaigning

In 1976, Hooker ran for a United States Senate seat, opposed in the Democratic primary by state Democratic Party chairman Jim Sasser, a Nashville lawyer. The campaign lacked the energy of Hooker’s previous bids for the governor’s office.

In fact, the same 2002 article in The Nashville Post that praised his 1966 campaign as one of the state’s best ever described Hooker’s efforts a decade later as “horrible.”

The Post wrote: “Hooker says that on the advice of pollster Pat Caddell, now creative consultant for the NBC show The West Wing, he barely campaigned at all. Convinced that the more Hooker campaigned the more anti-Hooker sentiment would materialize (Hooker was intimately tied to the Minnie Pearl Fried Chicken debacle), Hooker says that Caddell urged him to lay low against the underfunded, comparatively unknown Sasser. Heeding Caddell’s advice, Hooker began his mornings with a mixed drink and a relaxing rest poolside at the Arden Place condominiums in Green Hills.”

Sasser won the primary election, then defeated Republican Bill Brock in the general election.

At that point, Hooker was still three years away from one of his greatest political victories – but it didn’t occur at the polls. In 1979, Hooker joined Brownlee Currey and Irby Simpkins in purchasing an ownership interest in The Nashville Banner, at the same time The Tennessean was being purchased by Gannett Co. As part of the arrangement, Hooker became The Nashville Banner’s publisher.

After years of being opposed by The Nashville Banner politically, Hooker said he remembers the satisfaction he felt the first time he walked into the newspaper’s office as publisher.

“The gasp you could hear (all the way) down in Union Station when they saw who the new man was,” Hooker said.

Hooker’s involvement with The Nashville Banner didn’t last long, though. In 1982, he sold his stake in the business because he couldn’t get along with Simpkins.

While he continued to pursue other business interests, Hooker made several other unsuccessful bids for public office. He was selected as the Democratic Party’s nominee for governor again in 1998, but lost to Republican Don Sundquist. He lost an election for a seat in Congress in 2002 and an election for a Chancery Court judgeship in 2004. In 2006, he simultaneously ran for U.S. Senate and for governor, finishing third in the Senate Democratic primary and second in the gubernatorial Democratic primary. He also ran unsuccessfully as an independent candidate for governor in 2014.

In most of his later campaigns, Hooker raised little or no money and did little campaigning. He said that he didn’t really expect to win those races, but used them as platforms to draw media attention to issues he felt were important, including campaign contributions made by out-of-state donors and contributions provided to judicial candidates by attorneys.

‘The Lone Ranger’

In addition to running for public offices, he also appealed to the courts to bring about reforms in areas such as campaign finance and the judicial selection process.

Hooker filed numerous lawsuits on constitutional grounds. As a direct descendant of William Blount, Tennessee’s first territorial governor and one of the authors of its first state constitution, Hooker said he felt a special responsibility to correct what he saw as inconsistencies in the law.

“When I didn’t get elected, I saw myself as a guardian of our constitution,” Hooker said. “I concluded that if I didn’t do it, who would?”

Hooker said practicing attorneys risked hurting their careers by championing issues such as prohibitions on campaign contributions from lawyers to judges or popular elections for appellate court judges. However, as someone who didn’t have a very active law practice but knew the law, Hooker thought he was in a good position to raise those issues.

“I was the Lone Ranger,” Hooker said.

While Hooker considers his work on judicial reform as his greatest accomplishment, he had little success bringing about change through his lawsuits. The courts frequently ruled against him, which prompted more lawsuits in other courts.

In 2003, the Davidson County Circuit Court imposed sanctions on Hooker, including a provision that if he filed any lawsuit alleging a violation of the constitution, a special master would have to review that lawsuit to determine if it was frivolous.

Five years later, the Davidson County Chancery Court ordered Hooker’s law license suspended for 30 days following a state Board of Professional Responsibility hearing into a complaint that his lawsuits were frivolous. The board had recommended Hooker be censured for, among other things, describing a sitting judge as corrupt and dishonest.

In its findings and conclusions when assessing the 30-day suspension, the Chancery Court wrote: “The gravamen of his argument is that the Respondent (Hooker) is discharging his role as an attorney representing the Tennessee Constitution. He insists his lawsuits are not frivolous, but his actions are based on his perceived role as a ‘whistle blower.’ Respondent further proclaims that if in the discharge of these duties, he is censured, he would consider such censure a badge of honor.”

Don Quixote in a Stove Pipe Hat

Hooker’s recent history of fighting seemingly unwinnable battles on sometimes obscure legal issues have cast him in the minds of some people as a sort of caricature, a Don Quixote in search of new windmills to tilt. Known for wearing stovepipe hats, high collared shirts and cowboy boots, he’s frequently described as an eccentric.

Hooker is aware some people make fun of him or dismiss him as a gadfly, but he notes that the term ‘gadfly’ was originally coined to describe Socrates because of the philosopher’s frequent criticism of the ancient Athenian government. While having the respect of other people is important to him, Hooker said having self-respect is even more important – and he can only have it by staying true to his core beliefs and principles.

Hooker’s willingness to sue anyone who disagrees with him on the law – including high-ranking elected officials, law school classmates and friends – can irritate some people. But he’s also inspired loyalty among people like Hal Hardin, the volunteer on his 1966 campaign who now serves as his attorney.

Hardin said Hooker might have accomplished more in his legal and political careers if he had been more pragmatic and willing to compromise. However, Hardin added, a more measured approach wouldn’t have been true to the image he presented to all of his supporters in that first gubernatorial campaign.

Aubrey Harwell, another longtime attorney, said it’s hard to argue with Hooker because he holds to his convictions so tightly.

“The thing that’s unique about John Hooker is his passion and his obsessive compulsion with issues he cares about,” Harwell said. “…If he has a strong opinion, it becomes fact. He embraces it and reacts to it.”

Yet Winfield Dunn has found a lot to like in his former gubernatorial adversary. Dunn said he and Hooker didn’t part as friends following the 1970 election. However, Dunn recalled how Hooker used to joke, following that defeat, that he – not Dunn – was the “father of the Republican Party in Tennessee.”

So once when Dunn was invited to be the subject of a roast to raise money for the Cumberland River Rehabilitation Center, he asked Hooker to be one of the guest speakers.

“He came on and worked me over pretty good,” Dunn said.

The two men continued to run into each other over the years and a friendship formed. While they maintained their disagreement on most political issues, Dunn said he grew to appreciate Hooker’s intellect and integrity.

“In my heart, I feel a certain degree of remorse because he’s had so many disappointments,” Dunn said. “But I have so much admiration for him, too.”

In 2015, Hooker and Dunn continued to stay in regular contact and lived only a couple of miles apart from each other in Belle Meade.

In spite of the circumstances under which they met, Dunn said, “I treasure the time I’ve known John Jay Hooker. I’m a better person for it.”

One Final Campaign, Maybe

Hooker’s final political and legal battle is an extremely personal one. Diagnosed with melanoma that later spread cancer to other parts of his body, Hooker decided to champion what he calls “death with dignity,” the legal right for physician-assisted suicide.

In Hooker’s view, the choice of when to end one’s life is a fundamental freedom guaranteed by the Constitution.

“We should face up to that,” Hooker said. “We should recognize that’s an aspect of liberty.”

He lobbied the Tennessee General Assembly to pass a bill legalizing physician-assisted suicide in 2015. Also, through his attorney Hal Hardin, he filed a lawsuit seeking acknowledgement of a constitutional right to terminate one’s own life.

The General Assembly had taken no action on the legislation and the lawsuit was still pending at the time of this writing. Although his health has continued to decline, Hooker vowed to continue the fight on both fronts as long as he can.

“I don’t know how much time I have left, but I do know I want to invest that with vigor,” Hooker said. “I want to go out with my boots on, shaking my fist and trying to accomplish something.”

Hardin said Hooker’s last cause may become his most enduring legacy.

“He says this may be the most important thing he’s done in his life,” Hardin said. “He wants to do it not only for himself, but for millions of others. He wants to live to see something done about it. As a fallback, he wants to start a national debate…And he’s done that.”

Hooker, who says his body has been responding well to an experimental cancer drug, still hasn’t given up on one of his other signature issues, either. He’s weighing whether to once again challenge the legality of allowing attorneys to donate money to the political campaigns of judges.

“Since I haven’t found anyone else to carry that message, I hope to have enough time left to take one more bite at that apple,” Hooker said. “I want to live as long as I have a sense of being useful. When I can no longer be useful, it’s time for me to say good night.”

John Jay Hooker Jr.

Born: August 24, 1930

Died: January 24, 2016

Education: Montgomery Bell Academy (High School), University of the South in Sewanee, Vanderbilt University Law School

Career: Tennessee Politician, Tennessee Lawyer, Entrepreneur, and Social Activist

Notably:

- Part of the Vanderbilt graduating Class of 1957, which became renowned for the number of its graduates who went on to accomplish great things in their careers

- Became an assistant to Jack Norman Sr., one of the era’s legendary attorneys, in prosecuting the impeachment trial before the Tennessee State Senate of Raulston Schoolfield, a state judge from Chattanooga who was facing corruption charges

- Campaigned for John F. Kennedy presidential election

- Hired as Robert Kennedy’s special assistant

- Teamed up with popular country music singer Minnie Pearl to launch a chain of fried chicken restaurants

- Campaigned for Tennessee governor in 1966, 1970, 1998, 2006, and 2014

- Outspoken in his support of the Civil Rights Movement and in his opposition to the Vietnam War – both among the most divisive issues of the 1960s and early 1970s