Dunn developed an interest in politics at an early age. His father, Aubert Culberson Dunn, served as district attorney in Mississippi’s Lauderdale County during the 1930s. At the time, Dunn recalled thinking of the courthouse where his father worked as a mysterious place.

Winfield Dunn: From the Dentist’s Office to the State’s Highest Office, Making History Along the Way

by Blake Fontenay

September 12, 2016

"I view the citizen politician as one who inclines toward the political process, not as a means of economic opportunity or survival, but as an entry, on a temporary basis, for deeper involvement in the public affairs of the people."

Winfield Dunn, in his book, From a Standing Start: My Tennessee Political Odyssey

Winfield Dunn: From the Dentist’s Office to the State’s Highest Office, Making History Along the Way

Growing up in Meridian, Mississippi, Winfield Dunn recalls a time when he was around 7 or 8 and a playmate invited Dunn to join him in a swim across a pond on a cold March day. Dunn jumped into the water. The other boy didn’t. As a result, Dunn caught pneumonia and was bedridden for a week. During his long convalescence, Dunn said he learned a lesson.

"The thing I learned from that experience was not to take a stupid dare from someone I didn’t particularly care for anyway and not to be so gullible as a youngster," Dunn said. "That was quite a lesson for me and I was very remorseful as I look back to recall it."

More than three decades later, in 1970, Dunn faced a decision about whether to take a different kind of plunge. Although Dunn had never before held elected office and wasn’t particularly well known outside of his adopted hometown of Memphis, friends were urging him to run for governor, representing the Republican Party, which hadn’t held the office in 50 years.

A more cautious man at that age, Dunn made some trips to various parts of the state to gauge his prospects as a Republican candidate for governor. "I became convinced, based on the responses people gave me, that I ought to do it," Dunn said. "I tested the waters and they were warm."

Interest in Politics Began Early

Dunn developed an interest in politics at an early age. His father, Aubert Culberson Dunn, served as district attorney in Mississippi’s Lauderdale County during the 1930s. At the time, Dunn recalled thinking of the courthouse where his father worked as a mysterious place.

Dunn’s relationship with his father was complicated. On one hand, Aubert Dunn sometimes drank to excess, which scared his son. However, the father also had impressive political skills, including a resonant voice and an easy way of dealing with people. "Hearing him talk politics was especially appealing to me," Winfield Dunn said.

Aubert Dunn was a popular man in the community, who was frequently stopped on the street and drawn into conversations with friends. He would bring his son into those conversations by introducing him and asking him to say something intelligent. "He would put me on the spot like that with his friends and his purpose obviously was to find little inhibitions in me that could be released and I could be a spokesman, which I was on a number of occasions," Winfield Dunn said.

His father was elected to Congress in 1935 and the family spent a year living in Washington. Winfield Dunn earned money during that time selling newspapers and chatting up people in the elevator of the apartment building where they lived. His neighbors would tip him just for a chance to listen to the boy’s Mississippi accent.

After the family returned to Mississippi, Winfield Dunn worked odd jobs during high school, then enlisted in the United States Navy during World War II. After serving as a pharmacist’s mate and caring for the sick and injured at various locations around the country, the war ended and he came home.

He enrolled in college, first at Meridian Junior College and later the University of Mississippi. Dunn met his future wife, Betty Prichard, while he was campaigning for class president for the University of Mississippi’s school of commerce. He studied pre-law, but got his degree in banking.

After graduation, Dunn decided he wanted to get married rather than go to law school. Dunn’s father wanted him to enroll in dental school and become a dentist. In contrast, his father-in-law, who was a dentist himself, counseled Dunn to take a job selling insurance rather than following in his footsteps.

Dunn followed his father-in-law’s advice, at least initially, before enrolling at the University of Tennessee dental school in Memphis. After graduating, he worked in his father-in-law’s dental practice for a few years before branching out on his own. Although running for public office wasn’t really on his mind during those years, that was about to change.

Gradually Increasing His Involvement

While Dunn was busy building his dental practice and raising a family, his political views began to evolve. Growing up in Mississippi during the 1930s and 1940s, just about everyone he knew was a Democrat. However, after moving to Memphis, some of the people he was meeting in his civic and social circles weren’t enchanted with the Democrats, who had held power throughout most of Tennessee for decades.

Dunn’s views were influenced by his concerns about the spread of Communism and his reading of Barry Goldwater’s book, "Conscience of a Conservative," which was a revelation to him. As a Sunday school teacher at Christ United Methodist Church in Memphis, Dunn began trying to relate scriptural messages to the current events of the day.

Dunn remembers one of his earliest forays into political activism came when the Memphis city government was debating whether or not to add fluoride to the water supply. As a dentist, Dunn saw the health benefits and was among those who successfully argued for the proposal.

Dunn passed on an early opportunity to get involved in the campaign of United States Senate candidate Andrew P. Taylor in 1960, partly because of Taylor’s weak handshake when they first met. (Offering a firm handshake was another of Dunn’s father’s early lessons.) Not long afterward, friends were encouraging Dunn to run for Congress himself, a suggestion that "amazed" him when he first heard it. The idea wasn’t quite as enthusiastically received by his closest advisor, though.

"I took that amazement home to my wife, who very wisely said, ‘that’s the silliest thing I ever heard of, you with a dental practice,’" Dunn recalled. "She talked me out of even thinking about it. But that was kind of a start."

But it wasn’t long before the political bug bit Dunn again. He was encouraged by friends to run for a seat in the state legislature. Although West Tennessee was still a Democratic stronghold, the Republicans wanted to put up a slate of candidates so the Democrats in the race wouldn’t be uncontested.

Dunn decided not to pass on the opportunity to be part of that Republican slate because, as he put it, "competition makes a better product." While the Republicans were defeated as expected, Dunn enjoyed the time he had spent on the campaign trail.

Dunn ran for chairman of the Shelby County Republican Party in 1964, challenging Leo Cole, a former neighbor of his. In the election for the chairmanship, Cole was favored by party members who were more or less satisfied with the status quo. Dunn saw himself as part of the party’s new guard - known as the Republican Association – which was intent on growing Republican influence rather than being content to serve as token opposition to the Democrats.

"We were growing," Dunn said. "We were jockeying for power in the local political environment. We were successful in taking control of the Republican party out of old hands that had controlled it forever and that was a very exhilarating time."

Growing in Political Strength

In the early 1960s, Republicans were becoming more competitive with their Democratic rivals in races across the state. In 1962, the United States Supreme Court ruled that congressional districts had to be apportioned according to population, which created new opportunities for Republicans in some areas. Prior to that time, the courts had mostly taken a hands-off approach toward reapportionment issues, deeming them to be political decisions rather than judicial ones. In 1966, Howard Baker became the first Republican from Tennessee to win a seat in the U.S. Senate since Reconstruction.

By that time, Democrats were facing troubles within their party. For much of the first half of the 20th century, Democratic politics in Tennessee had been dominated by a political machine run by E.H. "Boss" Crump of Memphis. After Crump’s death in 1954, his supporters had continued to hold power, but their grip had become tenuous by the mid-1960s, according to Theodore Brown, a senior lecturer in the University of Tennessee political science department.

"Dunn came along at a time when there was growing division in the Democratic party," Brown said. "More progressive groups of Democrats were challenging the conservative views of Crump supporters. In my view, the defeat of the Crump machine led to the formation of a healthy two-party system in Tennessee."

In that political climate, Dunn sensed an opportunity for Tennessee to elect its first Republican governor since 1920. Although his term as Shelby County Republican Party chairman had ended in 1968, he thought there was a chance to elect a Republican governor if the party’s growing number of supporters in West Tennessee united behind a single candidate.

But finding that candidate turned out to be tougher than Dunn had figured. In 1969, Dunn recalls being flattered when Republican Bill Brock mentioned him as a potential gubernatorial candidate during a political rally.

"I left the meeting feeling complimented," Dunn wrote in his book, From a Standing Start: My Tennessee Political Odyssey. "(Brock’s) words, casually spoken, became riveted in my memory. Of course, nothing changed outwardly, but I began to fantasize occasionally about greater involvement. It was stimulating to think about such things, but fantasy was the only appropriate word for those thoughts. I had my work cut out for me with dentistry and my family, period."

Still, the idea never completely left Dunn. In late 1969, he began to travel around the state to see how well he might be received as a candidate. While Dunn was encouraged by the feedback he got on most of his trips, one led to a political feud that lasted throughout his political career.

During a stop in Johnson City, Dunn gave an interview to a newspaper reporter. The next day, the reporter reported – erroneously – that Dunn had already declared himself as a candidate for governor. At the time, Dunn was still trying to make up his mind about running. But the newspaper article raised the ire of Jimmy Quillen, the Republican congressman who represented that part of the state.

Quillen wasn’t happy Dunn had come to his congressional district, ostensibly to campaign, without checking with him first. "From the beginning, Quillen was a problem," Dunn said.

Lots of other people were supportive, though. Harry Wellford was an attorney and a friend who managed Dunn’s primary campaign and served as an advisor. Wellford, who later became a judge on the U.S. Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals, said Dunn was skilled at connecting with people on the campaign trail.

"He just had a natural charm or magnetism that appealed to people," Wellford said. "He’s just a very likeable person. He has more personal charm than just about anybody I know and I’ve known a lot of politicians in my lifetime."

Dunn finally decided to enter the race in April of 1970, just a few months before the primary election. "If we had known all of the obstacles we’d face as the campaign unfolded, we probably wouldn’t have had the courage to undertake it," Dunn said. "I decided in April of 1970 to be a candidate. Well, that was a little bit ludicrous because the primary election was in August and here I was, a complete unknown."

Dividing and Conquering

His primary opponents were not unknowns, however. They included William Jenkins, speaker of the state House of Representatives, Claude Robertson, former chairman of the state Republican party, Maxey Jarman, an industrialist, and Hubert Patty, who had been the party’s nominee in 1962.

Jarman, a Nashvillian who was retiring as chief executive officer of Genesco, Inc., tried to convince Dunn that if a West Tennessean and a Middle Tennessean both ran for governor, that would guarantee the election of one of the other candidates from East Tennessee. Jarman asked Dunn to support him in the 1970 race, in exchange for a pledge that Jarman would support Dunn four years later.

Dunn saw the dynamics of the race differently. As the only candidate from West Tennessee, Dunn hoped to capture most of the vote there while the other candidates split up the vote in other parts of the state. When Dunn refused Jarman’s offer during a meeting with Jarman and John Hazelton, one of Jarman’s supporters, Hazelton reportedly swore at Dunn and ordered him to get out of the race. The meeting ended abruptly.

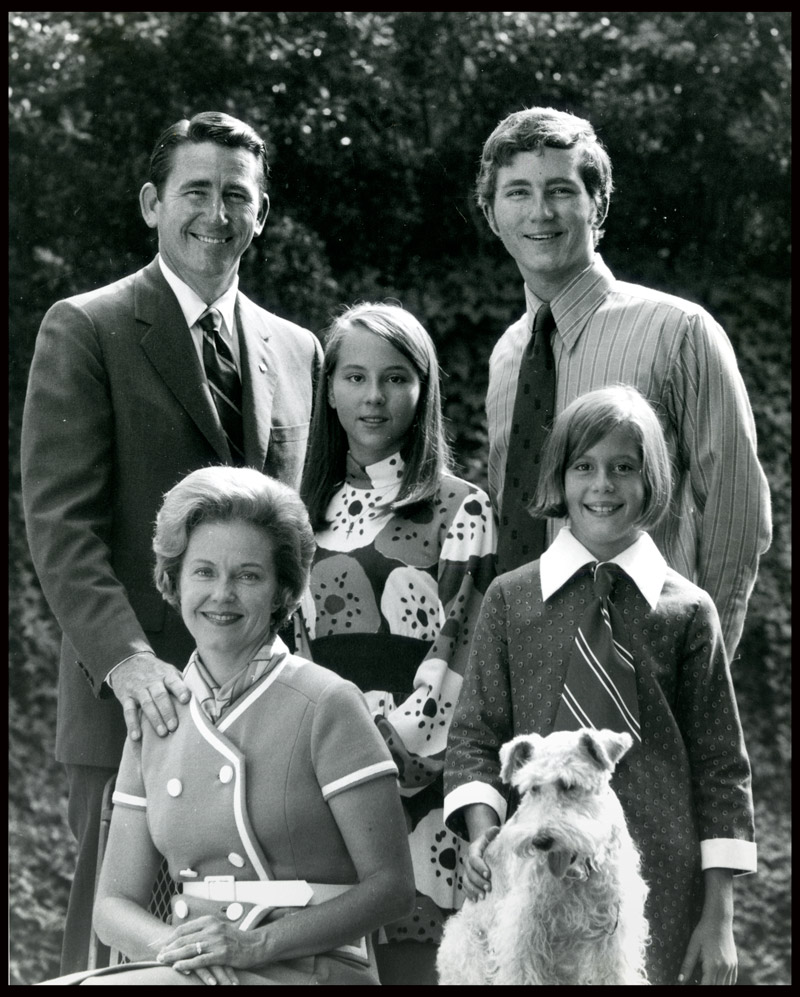

When Dunn announced his candidacy, he made a promise to unify the state’s three grand divisions one of his major campaign themes. Dunn began traveling across the state, asking Betty Dunn to attend many of the campaign events in West Tennessee while he worked on building contacts in East Tennessee.

Dunn’s relations with Congressman Quillen didn’t improve. Quillen was supporting William Jenkins, the speaker of the House of Representatives. Dunn said Quillen’s supporters continued to criticize him because Dunn refused to "bow down" to Quillen by checking with the congressman before each of his visits to East Tennessee.

His opponents mocked Dunn’s lack of political experience and name recognition, spurring the catchphrase, "Dunn Who?" Dunn’s campaign countered that with the slogan: "It can be Dunn – it must be Dunn – it will be Dunn!"

Dunn also found creative ways to mobilize different groups of supporters to help his cause. These included the "Dunn Dollies," a group of attractive young women who attended many campaign events, and the "Dentists for Dunn," a group of people from his own profession who got behind his campaign.

Bob Hutton, a senior lecturer of history and American studies at the University of Tennessee, said Dunn also benefited, as other Republican candidates in the upper Sun Belt did, from an in-migration of Republicans from the Northeast and Midwest during the late 1960s that continued into the 1970s. "He was part of a trend in the upper South," Hutton said. Although the Civil Rights Movement and the Vietnam War had created a tremendous amount of upheaval in the country, Hutton said Dunn projected a stability many voters were apparently seeking. "He kind of portrayed himself as the businessman’s candidate."

When the primary ballots were cast in August, Dunn’s theory about consolidating the West Tennessee vote proved to be correct. While the other candidates split the votes among themselves in other parts of the state, Dunn won West Tennessee in a landslide to earn the right to compete in the general election.

Taking on a ‘Sun God’

Dunn’s foe in the general election was John Jay Hooker, a one-time aide to U.S. Attorney General Robert Kennedy known for his charisma and his electrifying speech making. Hooker had lost to Buford Ellington in the Democratic gubernatorial primary in 1966.

Although Dunn had never met Hooker before the 1970 campaign, a friend had pointed the Democratic candidate out two years earlier when both men were visiting the Belle Meade Country Club outside of Nashville. At the time, Dunn’s friend had confided that Hooker was arrogant, heavy-handed and shouldn’t be the kind of person elected as governor.

Dunn finally met Hooker face-to-face for the first time at a campaign event during the primary season in 1970 – an encounter that convinced Dunn he had his work cut out for him if both men won their respective nominations. "The moment I looked directly at him and put the voice with the man, I was in awe," Dunn admitted. "His face was almost bronzed, seemingly just off the beach at some sunny resort. His features were handsome and I was very impressed with what I heard and saw. He struck me as movie star quality."

Hooker later left the event in an entourage that included three long black cars, while Dunn’s transportation was a modest used car driven by one of his new volunteers, Bill Russell of Lenoir City. At that point, Dunn said, "my awe melted to irony."

And Dunn’s confidence got a boost after meeting Hooker at a subsequent campaign event. Dunn noticed Hooker was wearing makeup, which was starting to run on the hot sunny day. "I was amazed," Dunn said. "I realized that fellow had bronze makeup on his face when I saw him in Cocke County at the ramp festival and that he wasn’t some sun-drenched god, but that he was a human being who used makeup. Well, that gave me a chuckle. And I decided he might not be so tough after all if he were my opponent."

A Different Kind of Battle

After Dunn and Hooker won their respective primaries, Dunn’s campaign made some changes in preparation for the general election. One of those changes was bringing in Lamar Alexander, who at the time had been serving on the staff of U.S. Senator Howard Baker, to serve as Dunn’s campaign manager for the general election.

Alexander said there was a steep learning curve to overcome among Dunn’s supporters, many of whom were relative newcomers to statewide politics. "There weren’t a lot of people who had been involved in statewide campaigns and knew what to do," said Alexander, a U.S. senator who also served as Tennessee governor and U.S. secretary of education during a long political career.

Alexander said Dunn had little in the way of a statewide organization at the outset of the general election campaign, but he also had no campaign debt. Dunn had relied heavily on friends and supporters from West Tennessee to help him during the primary, but Alexander said some of them had a hard time understanding that some adjustments were needed for the general election. "It was pretty hard to get them to put the campaign headquarters in Nashville," Alexander said.

As in the primary, Dunn’s personality became one of his strongest points while campaigning against Hooker, Alexander said. "I don’t think we’ve had a better pure candidate than Winfield Dunn," Alexander said. "Winfield Dunn is the kind of person who would talk to everyone in the elevator."

Dunn said he had few differences with Hooker on the issues during the campaign. "It became more a personality contest," Dunn said. In that area, there were sharp contrasts between the two men. Dunn was often described as plainspoken and humble, while Hooker came across as brash and flamboyant.

Alexander said Hooker challenged Dunn to debates "because he didn’t think Dunn knew the issues." However, Alexander said, Dunn acquitted himself well during those debates, which helped his cause.

Hooker’s campaign was hampered by other factors. Governor Buford Ellington, his rival in the 1966 campaign, didn’t endorse him. Many of the "old guard" Democrats were apparently willing to cross party lines to support Dunn rather than cast their ballots for Hooker.

Also, Hooker was under scrutiny during the campaign season by the federal Securities and Exchange Commission for financial record keeping related to a chain of fried chicken restaurants he co-owned with country music singer Minnie Pearl. The commission’s investigation centered on whether the restaurant chain had improperly "cooked its books" by reporting all franchise fees owed to it as income, as opposed to only the fees that had actually been collected.

In a 2015 interview, Hooker said he relied on his accountant’s advice in reporting the full amount of fees owed in the chain’s financial statements. The commission’s investigation concluded after the election was over, without any charges being filed against Hooker or the restaurant chain.

Dunn’s public image provided a sharp contrast. Shelby County Mayor Mark Luttrell, whose father served as Dunn’s corrections commissioner, said Dunn "had a very positive, very clean public personality."

Dunn got a small measure of negative media about an assault charge against him that had been dismissed years earlier. In Dunn’s telling of the story, he got into an argument with a hardware store owner who had been berating one of his employees. The store owner kicked Dunn in the leg. Dunn punched the man, who pulled a gun, called police and later swore out a warrant for Dunn’s arrest. The charges were dismissed, although when the story came out during the campaign, the media reports indicated that Dunn had failed to show up for a court appearance.

"Several years later, I was to learn that the court record of the warrant and hearing before Judge Weinman had been mysteriously altered to indicate that I failed to show at the appointed time," Dunn wrote in his book. "I can only assume that the Hooker people turned to some Democrat person in the Memphis City Hall and had him or her alter the record."

In any case, the report about the arrest had little impact on the election’s outcome: Dunn defeated Hooker to become Tennessee’s first Republican governor in 50 years. (Although their campaign had been hard fought, years later Dunn and Hooker struck up a friendship that lasted until Hooker’s death.)

A Steep Learning Curve

After winning the election, Dunn had to quickly turn his attention toward the preparations he needed to make to govern the state. In previous years, the Democratic nominee was all but assured of winning the governor’s race, which meant more time to prepare. Since Dunn had to wait until after the general election in November of 1970, he had only a few weeks afterward to prepare.

Alexander, who stayed on as part of Dunn’s transition team, said lots of Republicans expected to be rewarded with jobs since one of their own was taking the chief executive position. "Managing the patronage expectations was sometimes difficult for the first Republican governor in 50 years," Alexander said.

Dunn credits outgoing Governor Buford Ellington and his staff for providing valuable assistance during the transition. As soon as the primaries were over, Ellington realized that either Dunn or Hooker would be coming into the job without previous experience holding elected office or working in state government, so he provided as much help as he could.

Even with that assistance, Dunn realized that he had much work to do. "Winfield connected readily with the people who knew the ropes," said Harry Wellford, Dunn’s friend and manager of his Republican primary campaign. "He had the attitude of knowing he was a neophyte and needed to learn and learn fast."

While Dunn hired some new people after taking office, his staff was a mix of Democrats and Republicans, said Mary Clement, a Democrat who took a job in the state’s personnel office after the election. Clement, who had worked as a volunteer during Dunn’s general election campaign, said his positive demeanor and tendency to focus on running government efficiently made him a less polarizing figure than he could have been.

"He just had the ability to look people in the eye and smile," Clement said. "A smile just goes a long way in life."

Clement’s future husband, Bob, also had dealings with Dunn. Bob Clement, a Democrat who later became a U.S. congressman, served on the state’s Public Service Commission during Dunn’s term as governor. "I worked with Governor Dunn very well," Bob Clement said. "We never had any problems. It was a pleasure to work with him."

‘An Era of Partnership, Not Partisanship’

In fact, during his inauguration speech, Dunn had promised "an era of partnership, not partisanship." Dunn did not reappoint Ellington’s education commissioner, Howard Warf, a strong partisan Democrat. However, he did reappoint several other members of Ellington’s administration. He also appointed Maxey Jarman, one of his former primary opponents, to head a committee of select businessmen that did an in-depth study of the administrative practices of state government.

In order to accomplish his goals, Dunn knew he would need support from a legislature controlled by Democrats who were unaccustomed to working with a Republican chief executive. "Many Democrats could hardly believe that (his election) had happened," Dunn said.

Lamar Alexander said Dunn and the legislators had to go through a period of adjustment. "That was new for him and new for them," Alexander said. "He was not experienced in legislating or governing...(And) they had to get used to the inconvenience of dealing with a Republican governor. It was really the beginning of the two-party system. Tennessee had been as Democratic then as it is Republican now."

Even before Dunn took office, the legislature had begun asserting more independence from the executive branch of government, meeting every year instead of every other year and forming a fiscal review committee to give the governor’s budget proposals more oversight.

Investing for the Future

Although he had campaigned as a conservative Republican, one of Dunn’s first major decisions as governor was to ask legislators for a half-cent sales tax increase. "I had to ask for a tax increase because we were running into a very large deficit at the end of Gov. Ellington’s term," Dunn said.

Dunn had actually asked for a bigger sales tax increase to fund his plan to expand kindergarten education to every public school in the state. The legislature didn’t want a bigger increase, so it took longer for Dunn to reach that goal. By his final year in office, kindergarten was available in all public schools.

Charles Crawford, a history professor at the University of Memphis, said Dunn worked to unify the three grand divisions of the state and fairly allocate state government spending to each of them. Theodore Brown, a senior lecturer at the University of Tennessee department of political science, noted that Dunn also created a number of new departments within state government. These included the Department of General Services, which oversees spending to private contractors for goods and services, and the Department of Economic and Community Development, which recruits new businesses to Tennessee. Those departments continue to operate to this day.

Dunn said he was particularly proud of his administration’s decision to create the Tennessee Housing Development Authority, which helps people qualify for affordable home loans. Dunn’s administration also invested substantial amounts of money in roads, mental health care facilities and other projects he felt were necessary.

Although his administration spent money on a number of new initiatives, Dunn doesn’t see that as being inconsistent with his conservative principles. At the time, Dunn said, the state’s budget was only about $1 billion, compared with about $40 billion today, and there were unmet needs that had to be addressed. "I was looking at an entirely different situation," Dunn said.

Dunn was generally regarded as cool and level-headed by those who worked with him. He demonstrated those traits when the owner of a dry cleaning business in Memphis who was distraught over his tax bills took a state revenue collector hostage at gunpoint. The gunman was demanding to speak with the governor in person so, disregarding the advice of some of his advisors, Dunn flew to Memphis. In a telephone conversation, Dunn told the gunman that he wouldn’t speak with him face-to-face unless he surrendered his weapon and let the hostage go. The gunman granted Dunn’s requests and Dunn kept up his end of the bargain by meeting with him. In telling the story years later, Dunn does so with almost a casual shrug, claiming there was nothing heroic about what he did.

Charles Crawford, the University of Memphis history professor, said Dunn’s administration also distinguished itself by its lack of corruption. Prior to Dunn’s arrival in Nashville, Crawford said, "there was a great deal of corruption in government. It was just normal. They (Dunn’s people) had no knowledge of how things had been done in the past."

Making Tough Choices

Some of the decisions Dunn made were unpopular. He wanted to build a state prison near Morristown, which local residents opposed. He opposed construction of the Tellico Dam. He supported the construction of Interstate 40 through Overton Park in Memphis.

And, in a move that rekindled his rivalry with Congressman Jimmy Quillen, Dunn vetoed funding to build a new medical school at East Tennessee State University. Although the legislature overrode his veto and provided the funding, Dunn’s stance angered many East Tennesseans.

Looking back with more than 40 years of hindsight, Dunn said he has few regrets about the decisions he made then. For example, he said the Interstate 40 route through Overton Park was the best available path for the federal highway, even though it would have disrupted a community asset that many Memphis residents treasure to this day.

Because that route wasn’t chosen, a bypass loops around the northern and southern parts of the city before reconnecting with Interstate 40 in downtown. Dunn believes that has taken its toll on the city’s economic development efforts. "I see it (the bypass) today as a burden Memphis didn’t need to bear," Dunn said. "I think it probably has a good bit to do with the fact that downtown Memphis has failed to continue to grow with the times."

As for the medical school, Dunn said he still believes it wasn’t necessary to spend money for a medical college at East Tennessee State when there were other educational options elsewhere around the state.

Dunn remained a strong supporter of President Richard Nixon through most of his term. Dunn and U.S. Sen. Bill Brock served as co-chairmen for Nixon’s re-election campaign in Tennessee in 1972. Dunn continued to defend Nixon through most of the Watergate investigation. The Republican Governors Association, which Dunn chaired, hosted Nixon for a conference in Memphis. At the conference, Nixon promised that no new revelations about Watergate were going to surface. The next day, news reports detailed gaps in the tape recordings that were at the center of the controversy. Dunn was disappointed to learn about the gaps in the tapes and later admitted he had been wrong in defending Nixon.

Life After the Executive Office

Dunn left office in 1975 to mainly positive reviews in the state’s newspapers. As his four-year term was winding down, The Knoxville Journal speculated that he might even be a vice presidential candidate on a future Republican ticket.

Instead of seeking another political office, Dunn decided to make his move to Nashville permanent and took a job managing government and public relations for Hospital Corporation of America, known as HCA. Dunn remained at HCA for the next 10 years.

In 1986, he ran for governor again. After winning the primary, he faced Ned Ray McWherter, the Democratic speaker of the state House of Representatives, with whom Dunn had worked during his tenure as governor.

However, some of Dunn’s more controversial decisions may have cost him votes, particularly in East Tennessee, and McWherter won the general election. Shelby County Mayor Mark Luttrell, who considers Dunn a political role model, doubts Dunn would have made different decisions during his first term if he knew the potential long-term political consequences. "He made some decisions while he was governor that may have hurt his political career," Luttrell said. "(But) that was Winfield Dunn."

Dunn made investments and served on a number of corporate boards, but he never ran for public office again. He has remained an "elder statesman" for the Republican Party, continuing to attend political events as recently as this year.

Asked about his proudest accomplishment as governor, Dunn began to list several achievements, including the statewide kindergarten program, the creation of the Tennessee Housing and Development Authority and the Department of Economic and Community Development and the centralizing of the state’s purchasing system under the Department of General Services.

Finally, he settled on a more "big picture" view of his four years in office. "I would say that during my administration, we demonstrated to the people of Tennessee that the Republican party could be a constructive, productive element and the Republican party has fared very well in the years since my term," he said.

On that point, many scholars and political observers seem to agree. "He initiated a two-party system in Tennessee," said Charles Crawford, the University of Memphis history professor. "For 100 years, from 1870 to 1970, Tennessee had been a one-party state."

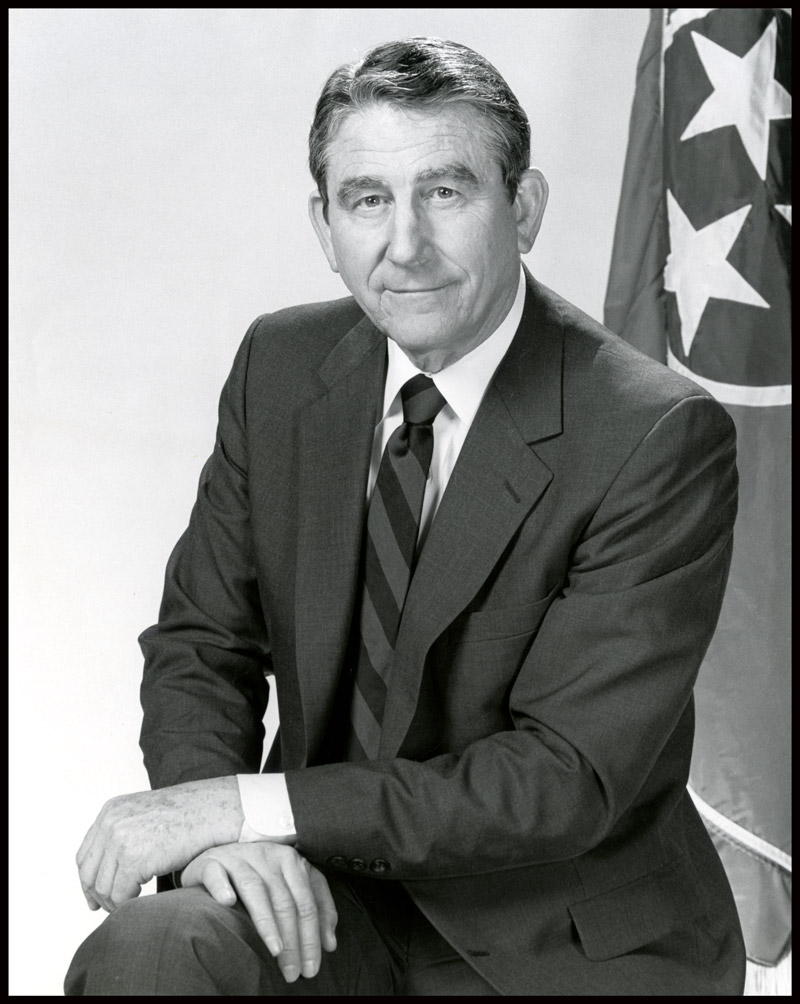

Bryant Winfield Culberson Dunn

Born: July 1, 1927

Education: University of Mississippi and University of Tennessee Medical School

Career: Tennessee governor from 1971 to 1975, dentist, health care executive

Notably:

- Tennessee’s first Republican governor in 50 years

- Successfully lobbied for kindergarten at public schools across Tennessee

- Centralized the state’s purchasing system

- Restructured state government, creating the Department of Economic and Community Development, the Department of Banking, the Department of General Services and the Tennessee Housing Development Agency, among others